Ever since Marc Andreessen published ‘The Techno-Optimist Manifesto‘ on 16 October 2023, I have wanted to get one particular opinion on it. Here is ChatGPT (4o)’s response to a prompt asking for a critical analysis:

1. Introduction and Context

Marc Andreessen’s Techno-Optimist Manifesto is a polemical document that seeks to reassert the virtue and necessity of technological progress in the face of what he identifies as a pervasive pessimism. Published in 2023 by the venture capitalist and co-creator of Netscape, the text is structured as a series of declarative statements, ranging from sweeping axioms (“We believe that growth is good”) to cultural provocations (“Love technology”). It positions itself as a corrective to prevailing anti-growth, anti-tech sentiments, drawing a stark contrast between progress and what Andreessen views as the regressive forces of “decadence, demoralization, and despair.”

2. Rhetorical Style and Form

The manifesto’s rhetorical strategy is assertive, even defiant. Andreessen adopts the language of revolutionary manifestos, employing repetition, direct address, and imperative commands. The staccato prose and aphoristic declarations evoke both Ayn Rand’s didacticism and Silicon Valley’s penchant for disruption. This style serves two primary functions:

-

Mobilization: The text aims to galvanize its readers — likely tech entrepreneurs, investors, and innovation enthusiasts — into an ideological camp of progress and defiance.

-

Boundary-Setting: It demarcates insiders (“builders,” “techno-optimists”) from outsiders (critics, bureaucrats, academics), echoing the us-versus-them mentality often seen in libertarian or accelerationist writing.

However, this same rhetorical force also undermines its persuasive efficacy in broader intellectual contexts. The lack of nuance, evidence, or engagement with opposing arguments may energize adherents but does little to persuade skeptics.

3. Philosophical and Ideological Framework

Andreessen’s worldview is grounded in several core assumptions:

a. Teleological Progress

The manifesto rests on a linear, quasi-teleological notion of progress. Technology is presented not just as a tool but as the driving force of moral and civilizational improvement. In this view, all human advancement — from health to freedom — is reducible to technical innovation.

Critique: This collapses complex social and political developments into a single axis of technological capability. It ignores historical counterexamples where technological advances coexisted with exploitation, environmental destruction, or authoritarianism (e.g., industrial capitalism, surveillance states).

b. Market Absolutism

Markets, in Andreessen’s view, are not only efficient allocators of resources but also moral arbiters. He sees capitalism as the engine of creativity and dignity, while regulators and public institutions are cast as enemies of progress.

Critique: This stance reflects a neoliberal orthodoxy that has come under increasing scrutiny post-2008. It neglects the role of state-funded innovation (e.g., the internet, GPS), public health systems, and democratic governance in shaping the conditions for technological progress.

c. Anti-Humanism in the Name of Humanism

Paradoxically, the manifesto celebrates the transcendence of human limitations while insisting that technology serves human flourishing. It promotes AI, automation, and even space colonization as unalloyed goods.

Critique: This techno-transcendentalism veers into a post-humanist logic that may ultimately displace rather than empower human agency. It also fails to account for who controls these technologies, for whom they work, and whose values they encode.

4. Engagement with Critics and Alternatives

Andreessen constructs a caricature of his critics: they are anti-growth, anti-energy, anti-human. This straw-man approach avoids engaging with the complex ethical, ecological, and socio-economic concerns raised by critical theorists, environmentalists, or ethicists of technology.

For example, scholars such as Langdon Winner and Sheila Jasanoff have long interrogated the political and ethical dimensions of technological design — not to reject progress but to demand accountability and inclusivity.

Likewise, degrowth theorists do not oppose technology per se, but question the sustainability and justice of infinite growth on a finite planet. Andreessen does not address these positions with any seriousness, dismissing them as irrational or malicious.

5. Utopianism and Its Limits

The manifesto is animated by a utopian vision of abundance, longevity, and empowerment. This echoes transhumanist and accelerationist aspirations for a post-scarcity society liberated by exponential technologies.

Critique: Utopian visions have historically played an important role in motivating social and technological change. However, when they ignore power dynamics, structural inequality, and ecological boundaries, they risk becoming ideological cover for technocratic elitism or capitalist expansionism.

Andreessen’s techno-utopia lacks any account of redistribution, democratic oversight, or the social contracts that bind diverse communities together. It is a vision of the future tailored to the winners of the current system.

6. Conclusion: Manifesto or Ideology?

Marc Andreessen’s Techno-Optimist Manifesto is best read not as a philosophical treatise but as an ideological document — one that reflects and reinforces a particular worldview dominant in certain sectors of Silicon Valley. It is a manifesto of power, faith, and disruption — but not of reflection, deliberation, or justice.

While it rightly celebrates human ingenuity and the transformative potential of technology, it does so through a lens that flattens history, marginalizes dissent, and elevates markets over democratic and ethical reasoning.

A truly constructive techno-optimism would need to embrace complexity, reckon with unintended consequences, and articulate a vision of shared progress — not just growth for growth’s sake.

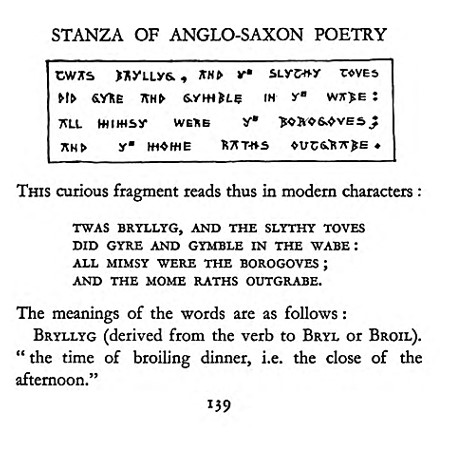

At one point, Andreessen offers a ‘paraphrase’ of an unspecified ‘manifesto of a different time and place,’ quoting these sentences: ‘Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Technology must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.’ The first two sentences come directly from maxim 7 of Filippo Marinetti’s ‘Futurist Manifesto‘ (1909). The third is re-written for Andreessen’s purposes. In the original version, maxim 7 ends with: ‘Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.’ So, for Andreessen, tech has become the new Futurist poetry. Again, I was curious to know what ChatGPT made of this.

Marc Andreessen’s allusions to The Futurist Manifesto of 1909, written by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, are crucial for interpreting the cultural and ideological aesthetics of his Techno-Optimist Manifesto. These references are not just rhetorical flourishes but reveal a deeper affinity between the two texts — in tone, intent, and underlying vision. However, they also raise critical questions about the political and historical resonances of techno-futurism.

Here’s a structured analysis of this connection:

1. Historical and Ideological Parallels

Militant Celebration of Progress

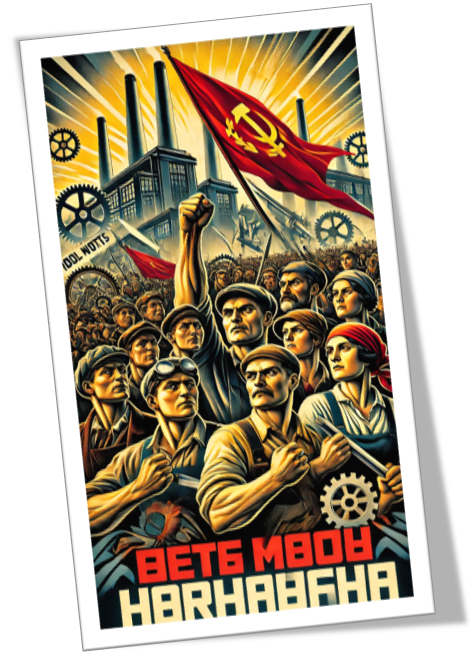

Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto was an incendiary rejection of the past, a hymn to speed, machinery, industry, violence, and masculine strength. It glorified modernity as a break from history’s weight and traditional values.

Andreessen’s text echoes this zeal: it positions technology as not just progressive but redemptive — a force of rupture that deserves quasi-religious veneration. His disdain for “limits,” “bureaucracy,” and “pessimism” channels Marinetti’s contempt for cultural conservatism and ethical caution.

Both manifestos see technological transformation as an existential imperative: it is not simply about tools, but about rebirthing society.

2. Aesthetic and Rhetorical Affinities

Manifesto as Weapon

The genre itself is key. Like Marinetti, Andreessen employs the manifesto form not to argue but to declare. There is no dialectic, only dogma. This style enacts the very ideology it promotes: forward motion without friction.

Provocation and Dichotomy

Andreessen, like the Futurists, uses stark dichotomies: progress vs. stagnation, builders vs. parasites, future vs. past. Such binaries are not designed to invite reflection but to incite loyalty — or rebellion.

“We are not victims,” Andreessen writes — echoing Marinetti’s “We want to glorify war—the world’s only hygiene”—both appeals to hardness, vitality, and will-to-power.

3. The Fascist Genealogy and Its Implications

Futurism and Fascism

It is important — and ethically necessary — to recall that Italian Futurism, especially in its later phases, directly aligned itself with Fascism. Marinetti was a vocal supporter of Mussolini. The Futurists’ worship of technology, speed, hierarchy, and violence fed directly into the aesthetics and ideology of authoritarian nationalism.

Andreessen’s manifesto does not advocate violence, nor does it engage with state power in the same way. But his techno-determinism, his disdain for “demoralizers,” and his quasi-Nietzschean exaltation of “builders” risk echoing this legacy. In elevating a small elite as humanity’s saviors, he edges toward a technocratic romanticism that excludes democratic deliberation and pluralism.

The ghost of Marinetti in Andreessen’s prose raises the specter of a technofascist temptation — progress without ethics, acceleration without consent, power without accountability.

4. What Andreessen Overlooks

If Andreessen consciously draws on the Futurist spirit, he does so without acknowledging the political and ethical disasters to which it contributed. There is no reflection on the lessons of the 20th century: on how technologies of progress were used in war, colonization, surveillance, and exploitation. Nor is there a recognition that uncritical reverence for innovation can become a vehicle for dehumanization.

A mature techno-optimism would grapple with these shadows. Andreessen, by invoking The Futurist Manifesto without qualification or irony, risks repeating its ideological blindness under a different banner.

Conclusion: An Inheritance with Dangers

Andreessen’s invocation of The Futurist Manifesto is more than stylistic homage. It reveals a shared modernist impulse: to tear down, accelerate, and transcend. But it also inherits Futurism’s pathologies — its glorification of elite willpower, its aesthetic of domination, and its political myopia.

To read Andreessen through Marinetti is to see not just a call to build, but a call to bulldoze — and to ask: Who decides what gets built, and who gets buried in the process?

and Henri-Jean Martin’s field-defining L’Apparition du livre (1958), the contributors were asked ‘to consider how the scholarly interest in print culture or the history of the book has developed since then’ and ‘to identify an individual, a group, a publication, a theme or an event from the past fifty years that has most significantly shaped your own work’ (Sharp 2008: 29). Two of my co-panellists chose key figures in the fields of bibliography and textual criticism, Harold Love and W. W. Greg; one focussed on the concept of ‘Material Culture’; and another on a 1985 conference on the history of the book in Renaissance Europe held in Tours, France. I opted for the French writer-philosopher Maurice Blanchot (1907-2003). This is the text of my statement, which appeared alongside the four others on the conference programme:

and Henri-Jean Martin’s field-defining L’Apparition du livre (1958), the contributors were asked ‘to consider how the scholarly interest in print culture or the history of the book has developed since then’ and ‘to identify an individual, a group, a publication, a theme or an event from the past fifty years that has most significantly shaped your own work’ (Sharp 2008: 29). Two of my co-panellists chose key figures in the fields of bibliography and textual criticism, Harold Love and W. W. Greg; one focussed on the concept of ‘Material Culture’; and another on a 1985 conference on the history of the book in Renaissance Europe held in Tours, France. I opted for the French writer-philosopher Maurice Blanchot (1907-2003). This is the text of my statement, which appeared alongside the four others on the conference programme: