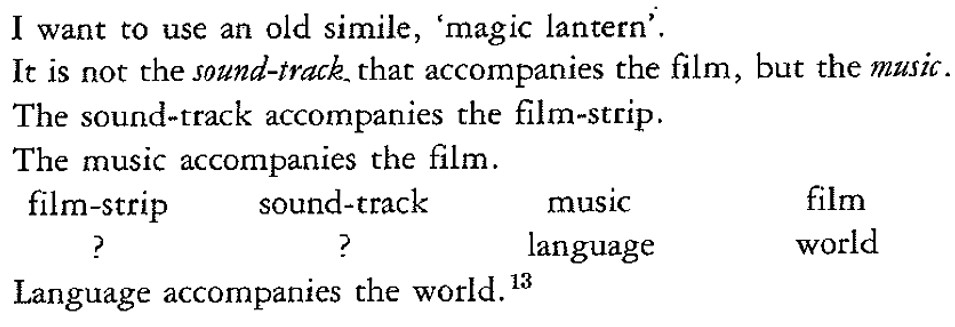

1. This illustration introduces a brief note in Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle (1979), a series of occasional conversations with Wittgenstein recorded by the Austrian philosopher Friedrich Waismann between 1929 and 1932 (p. 50). The note comes at the end of the entries for 22 December 1929. Given the precise nature of the illustration, the date is significant. What Waismann drew, no doubt at Wittgenstein’s prompting, was an example of the new optical sound-on-film technology which combined an audio-track with the visual frames on celluloid film. The first, called Phonofilm, patented in 1919, was soon overtaken by improved systems like RCA Photophone, initially exhibited in 1927. Since the first major ‘talkie’, The Jazz Singer (1927), used a different system with the sound recorded on a separate disc, the illustration reflected a detailed knowledge, again most probably on Wittgenstein’s part, of the latest technological developments in the film industry. The following statements then appear under the illustration:

2. There are several oddities about this gnomic record (prose-poem?), beginning with the fact that the ‘I’, no doubt the au courant Wittgenstein, begins with the ‘magic lantern’, a mode of visual projection developed in the 17th century, which was, of course, silent. Most probably he wanted to bring the ‘old simile’ into the new era of sound film — as Waismann’s heading for the entry intimated, the simile concerned ‘Language and World.’ So, again reading between the lines, which is pretty much where all the reading must happen here, the primary function of language as a bearer of knowledge is, like the old magic lantern, to picture the world. This effectively adds one more analogy to the many Wittgenstein used in the Tractatus (1921) to clarify his so-called ‘picture theory’ of language: he refers to tableau vivant, gramophone records, musical scores, models, hieroglyphic and alphabetical scripts, and more (see ‘Strip Teasy’ post).

3. The new sound film technology changed the terms of the analogy not simply by adding audio but by distinguishing two sets of relationships. First, there is technical relationship between the sound-track and the film-strip (as in the illustration); second, there is the experiential relationship between the music and the film. (Note: we pass over the more obvious links between sound-track and music, film-strip and film). Then we have the analogy with language and the world. As the two final statements and the pairings to the right of the four-part grouping indicate, this applies only to the experiential music-film connection. So ‘language accompanies [begleitet] the world’ as ‘music accompanies the film’. (Note: no mention of speech, the key element of the ‘talkies’).

4. So far, perhaps so good. But what about the question marks under film-strip and sound-track in the four-part grouping? They appear to create space for additional terms on the other side of the equation. Here it seems Waismann got the order wrong: presumably sound-track should come first, mirroring music, followed by film-strip, mirroring film. Are there any contenders? Two terms that might match language and world, making the updated magic lantern analogy do even more work?

5. It is impossible to be certain. Besides the cryptic nature of the statements, we can never be sure about the accuracy of Waismann’s reporting. (In this case, the translation — I am using Schulte and McGuinness’s English version — does not create further complications.) Yet, given the tenor of the conversations on that day in December 1929, during which Wittgenstein kept emphasizing how his thinking had changed in the eight years since the publication of the Tractatus, one possible pairing could be logical notation/sound-track, fact/film-strip, or maybe just name/track, object/strip. That said, if the question marks are not placeholders but queries expressing doubts about any viable options, then the terminology is not the issue. The key thing is to understand why, in this cryptic scenario, the experiential relationship (music/film) trumps the technical (track/strip).

6. Some of Wittgenstein’s other remarks provide a few suggestive clues. Earlier on the same day—assuming the notes are recorded chronologically—he commented:

I used to believe that there was the everyday language [Umgangssprache] that we all usually spoke and a primary language that expressed what we really knew, namely phenomena. I also spoke of a first system and a second system. Now I wish to explain why I do not adhere to that conception any more.

I think that that essentially we have only one language, and that is our everyday language. We need not invent a new language or construct a new symbolism, but our everyday language already is the language, provided we rid it of the obscurities that lie hidden in it. (45)

This sounds like Wittgenstein claiming he used to believe the task of philosophy was to create an ideal or logically perfect language, but now thinks it is only about clarifying ordinary language. In fact, he never made the first claim, though many philosophers at the time, including Bertrand Russell, believed he did (again, see ‘Strip Teasy’ post).

7. Yet, if we re-read these comments with the sound film analogy in mind, then a different possibility emerges. He once believed philosophers could gain special access to the projection room to see the technical workings of the primary phonofilm system, the optical sound-track and the film-strip, but now he thinks otherwise. Like ordinary moviegoers, all they have is the music accompanying the film, or, in the analogy, the lived experience of language accompanying the world. On this reading, the question marks are not placeholders (e.g. for logical notation/fact) but queries casting doubt on the idea of a primary language existing above or apart from the everyday version. When it comes to language and the world, there is only the music and the film.

8. This becomes a little clearer considering what Wittgenstein goes on to say about the limits of formal logic in a passage immediately following his remarks about everyday language being the only one we have.

There is nothing wrong with a symbol like ‘φx’, if it is a matter of explaining simple logical relations. This symbol is taken from the case where ‘φ’ signifies a predicate and ‘x’ a variable noun. But as soon as you start to examine real states of affairs, you realise this symbolism is at a great disadvantage compared with our real language. (46)

The reason?

It is of course absolutely false to speak of one subject-predicate form. In reality there is not one, but very many. For if there were only one, then all nouns and all adjectives would have to be intersubstitutable. For all intersubstitutable words belong to one class. But even ordinary language shows this is not the case. (46)

He followed this with a series of examples, beginning with the two statements ‘This chair is brown’ and ‘The surface of this chair is brown.’ ‘If I replace “brown” with “heavy”,’ he added, demonstrating the non-substitutability of adjectives, ‘I can utter the first proposition and not the second.’

9. In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein claimed ‘logic is transcendental’ (6.13) and used clothing metaphors to describe the logical form hidden under everyday language (4.002, and see ‘Strip Teasy’ post). In 1929, following developments in the film industry, he changed analogies not to reinforce the ‘old simile’ of the magic lantern, or, we could now add, of clothed bodies, but to challenge the underlying two-language view, anticipating the future directions of the Philosophical Investigations (1953) where he insisted that ‘nothing is hidden’ (435) and that ‘understanding a sentence is much more akin to understanding a theme in music than one may think’ (527).