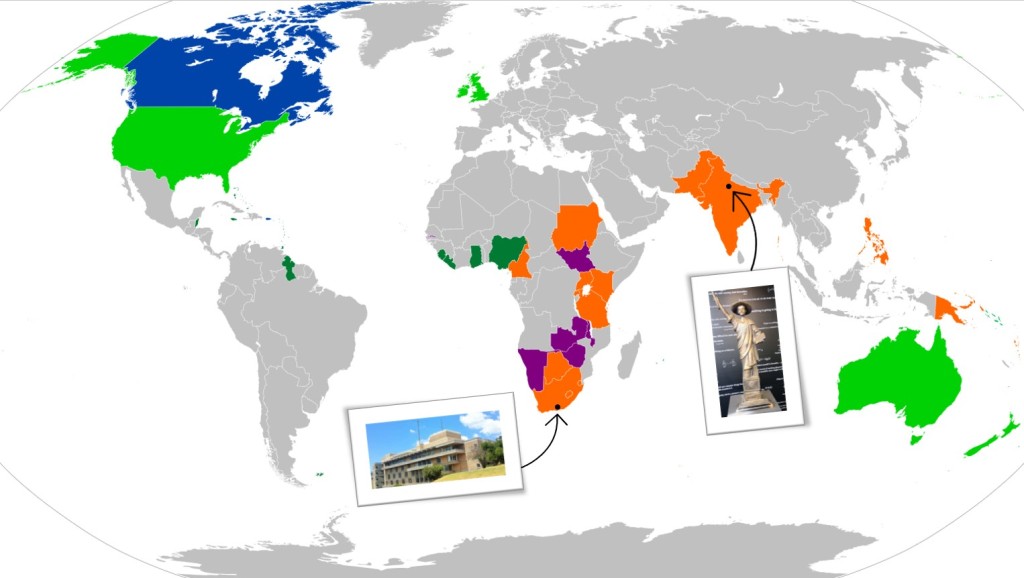

According to Wikipedia’s colour coding of the map above, India and South Africa are not part of the Anglosphere—the light green territories, including the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, where, despite being the majority language, English has no official status. India and South Africa are orange because they both recognize the language in law—English is one among 22 official languages in the former, one of 11 in the latter—and because it is widely used in education and public life.

Inevitably, this is a schematic and legalistic way of representing the many stories of English across the world today. To uncover the tangled histories of the language and its complex contemporary realities, we need a more grounded and localized perspective. Here I take a view from Makhanda, Eastern Cape, South Africa, site of the ‘1820 Settlers’ Monument’ (as it is still called), and from Banka, Uttar Pradesh, India, home to the Dalit ‘English Temple.’

The Settlers’ Monument

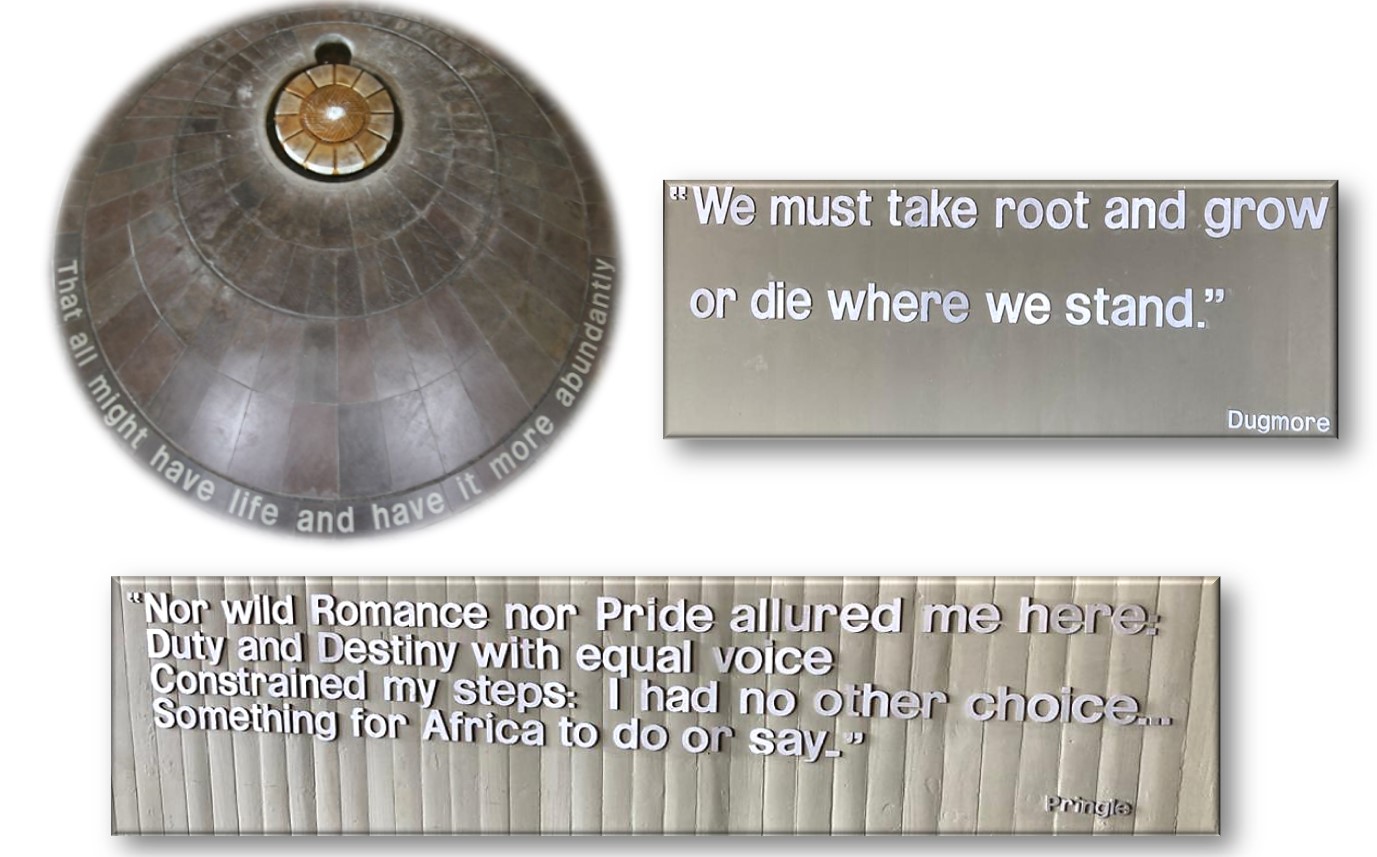

The 1820 Settlers’ Monument occupies a commanding position on a hill overlooking the city of Makhanda (population around 140,000). It is, in fact, adjacent to Fort Selwyn, a stone redoubt the British had located on the same spot for military purposes in the 1830s — hence Gunfire Hill. Modelled on the monolithic modernist design the American architect Louis Kahn developed in the 1950s, the vast 20,000-square metre, seven-level building includes a 1000-seat theatre, a 200-seat cinema as well as art galleries and conference facilities. Since it was opened in 1974, it has also been the venue for an annual festival of the arts. As its first publicity officer explained, the ship-like concrete, brick and glass structure—‘proudly dominating the landscape’—was intended to embody the iconic function:

As the use of the building had to be related to the contributions made by the British pioneers, the main functions are designed to concentrate on perpetuating the heritage bequeathed by the 1820 Settlers—the English language and the democratic traditions they brought with them—by means of an auditorium to be used mainly for English-language festivals and a conference centre that points to the democratic practice of debate and discussion. (Neville 1974: 12)

A plaque in the entrance, which pointedly speaks for the settler lineage in the possessive first-person plural, still makes the same point: the ‘facilities are open to all, to enjoy and enlarge our heritage of language and culture and to perpetuate our traditions of tolerance and freedom of speech.’ ‘It is perpetuating more than a language,’ the publicity officer concluded, ‘it is an ethos; a characteristic spirit; a heritage; an endowment’ (13).

Three conspicuously displayed quotations in the cavernous main foyer, one etched in stone around a central fountain, the other two rendered in large, brushed-steel letters on the concrete walls at the entrance, reiterate the message in more poetic terms. ‘That all might have life and have it more abundantly’, the fountain inscription reads, adapting Jesus’s parable of the good shepherd from the King James version of John 10:10. ‘We must take root and grow or die where we stand’, the writing on the first wall at the entrance declares, turning a past-tense observation the English missionary Henry Dugmore (1810-96) made in The Reminiscences of an Albany Settler (1871) into a present-tense injunction. Finally, a side wall at the entrance carries four lines from the end of ‘The Emigrant’s Cabin’, a 305-line ‘conversation poem’ by the Scottish writer, free-speech campaigner, and abolitionist, Thomas Pringle (1789-1834), who was a leading figure in the settler community during his brief six-year residence in the Cape:

Nor wild Romance nor Pride allured me here:

Duty and Destiny with equal voice

Constrained my steps: I had no other choice…

Something for Africa to do or say.

This comprises lines 137-39 of the poem, plus line 230, all spoken in the Pringle voice. ‘Thomas Pringle’ lives on as the name of one of the building’s primary venues as well. The cinema and main theatre are also named: the former after the writer, feminist, and anti-war campaigner Olive Schreiner (1855-1920); the latter after the poet, academic, and leading proponent of the Monument Guy Butler (1918-2001). There is some acknowledgement of local Xhosa heritage too, but only via a single figure who also exemplifies the success of missionary evangelism. The art gallery is named after Ntsikana (1780-1821), the first Xhosa prophet to propagate Christian beliefs.

For the Monument’s founders, the talismanic settler names and quotations did more than express what they considered the ‘characteristic spirit’ of the British legacy. Like the plaque declaring the facilities ‘open to all,’ they elevated their project above the brutally repressive realities of apartheid. ‘Inscribed in the flagstones of the floor of the impressive memorial foyer, around a perpetually bubbling fountain, are the words from St John’s gospel’ testifying to the Monument’s ‘openness and hospitality,’ the chair of the 1820 Foundation explained in 1991 (Neville 1991: 105). He was echoing his predecessors who had from the start insisted ‘this is no sectional or bombastic memorial’ (103).

Some details about the building’s history suggest otherwise. Two will suffice. First, a coincidence: the monumental tribute to ‘our traditions of freedom of speech’ opened the year the white-only, Westminster-style Parliament, another settler inheritance, passed the Publications Act, 1974, inaugurating a new, more repressive phase in the history of apartheid censorship. Second, an enabling condition: far from disdaining, or simply ignoring, the drive to commemorate the 1820 settlers, the state actively supported it from the start, in the end covering 80% of the final construction cost (R3.2 million of the R4 million total, around R200 million in today’s values) (Neville 1991: 64, 93). Indeed, for the state, the Monument was something of a propaganda coup—the publicity officer’s promotional piece about the opening was, accordingly, given a six-page, illustrated spread in S.A. Panorama (1956-1993), a state-run periodical designed to boost South Africa’s image at home and abroad (see images below). Evidently, any threat the founders’ claims about openness, tolerance, and free expression posed was outweighed by the endorsement their project gave to the state’s own racialized ethnolinguistic vision of apartheid South Africa as an essentially Anglo-Afrikaner polity, comprising an association of divinely ordained, separate volke, each with its own language and ethnic heritage.

The name and future of the Settlers’ Monument have been under review since 2015, outcome not yet known. In the meantime, the South African-born writer Zoë Wicomb has given Thomas Pringle and his legacy a trenchant fictional reassessment in Still Life (2020), pre-emptively re-setting the terms of the debate in ingeniously inventive ways (see ‘Other Writers’).

The Dalit Temple

Inaugurated in 2010, the Dalit Temple in the rural village of Banka (population around 8,000) was imagined as an altogether more modest structure. Planned to be located in the grounds of a private, Dalit-run school, it was envisaged as a single-story block covered in black granite, to be built for the sole purpose of housing a small bronze idol of ‘Angrezi Devi’ (literally, ‘English Goddess’), as her Hindi name has it. She is also known as the ‘Dalit Goddess’ or ‘Dalit Ma’ (‘Dalit Mother’). The fact that it was to be on private land is significant. Despite this, state officials still opposed its construction — one of many features distinguishing it from the Monument — so it remains a Temple of the imagination, though a replica was erected temporarily in Goa in 2021. Equally significant is the date on which the idea of the Goddess was first mooted: 25 October 2006. This marked the 206th birthday of Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-59), the colonial administrator who did most to entrench English as the primary language of elite education in British India, a process that began with his notorious ‘minute’ of 1835 — as it happens the year plans for the construction of Fort Selwyn were approved. Macaulay is not the only historical figure commemorated, however. As the leading proponent of the project, the journalist and activist Chandra Bhan Prasad, commented, the Temple is also dedicated, less provocatively, to the memory of Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956), the reforming Dalit jurist, economist, and political leader who played a key part in framing the Indian Constitution. ‘When it was being debated as to what should be the national language of India after independence,’ Prasad remarked, ‘Dr Ambedkar was the only national leader who vociferously batted for English’ (for more on these debates and the poet Arvind Mehrotra’s own inventive response to them, see Chapter 7 of Artefacts of Writing).

Modelled on the Statue of Liberty, the small bronze figure, designed by the Dalit writer and artist Shanti Swaroop Baudh, captures the myriad aspirations the Goddess embodies. As Prasad explained:

She holds a pen in her right hand which shows she is literate. She is dressed well and sports a huge hat—it’s a symbol of defiance that she is rejecting the old traditional dress code. In her left hand, she holds a book which is the constitution of India which gave Dalits equal rights. She stands on top of a computer which means we will use English to rise up the ladder and become free for ever.

This makes the Goddess the herald of a future in which the Dalit community will not just have been empowered through their proficiency in written English. They will have escaped ‘the caste-saturated languages of India which they habitually speak,’ as Sumathi Ramaswamy notes (314). The Goddess is not wholly anglicized, however: the computer-plinth on which she stands has on its screen the symbol of the Buddhist Dharma chakra, no doubt signifying the righteousness of her path, while also ensuring her call to English does not entail any form of Christianization—recall the quotation from the King James Bible in the Settlers’ Monument and the tribute to Ntsikana.

The quotations displayed on the wall behind the Goddess, in a replica displayed in Goa, also set the Temple apart from the Monument not least by eschewing the Christian ethnonationalist assumptions on which the latter was founded. Mixed in with an array of classic formulas from mathematics and physics—E=mc2, V-E+F=2, etc.—is a series of literary citations mainly from canonical English authors (Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Dickens, George Eliot, Emily Bronte, Orwell), but also from Yeats (Ireland), T.S. Eliot (US/UK), Harper Lee (US), and Atwood (Canada), and then, in translation, Homer, Sophocles, Márquez, Camus, and Dostoevsky (see full details below). So, in contrast to the Monument’s ethnic canon, the Goddess represents a multilingual tradition of world literature in English, which, as the quotations intimate, speaks to a constellation of fundamental rights and aspirations. Some point to the freedom the Goddess heralds (Sophocles: ‘free speech at least is mine’), some to the scientific attitude (Dickens: ‘Take nothing on its looks’), and others to the need to for an enlarged mentality (Lee: ‘You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view’) or to the dignity of self-sufficiency (Wordsworth: ‘bliss of solitude’). ‘This is the cry of emancipation,’ the manifesto on the first promotional poster declared, ‘this is the cry for English, the Dalit Goddess.’ The poster then encouraged Dalit parents to ‘lean poetically’ to their newborns: ‘First the left ear/Whisper now/‘A-B-C-D’/Turn to the right/Whisper/‘1-2-3-4.’

Temple Wall Quotations

Let me not then die ingloriously and without a struggle, but let me first do some great thing that shall be told among men hereafter.

(Homer, Iliad, c. 800BCE)

But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.

(George Orwell, ‘Politics and the English Language’, 1946)

Perhaps one did not want to be loved so much as to be understood.

‘Who controls the past,’ ran the Party slogan, ‘controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’

Until they become conscious they will never rebel, and until after they have rebelled they cannot become conscious.

(George Orwell, Nineteen-Eighty Four, 1949)

What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult to each other?

It is always fatal to have music or poetry interrupted.

(George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1871)

Take nothing on its looks; take everything on evidence. There is no better rule.

(Charles Dickens, Great Expectations, 1861)

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

(William Wordsworth, ‘I wondered lonely as a cloud’, from Poems, 1807)

You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view – until you climb inside his skin and walk around in it.

The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule is a person’s conscience.

(Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird, 1960)

Off my face! You’re the life principle,

more or less, so get going

on a little optimism around here.

Get rid of death. Celebrate increase. Make it be spring.

(Margaret Atwood, ‘February’ from Morning in the Burned House, 1995)

It is enough for me to know that you and I exist in this moment.

(Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967)

If something is going to happen to me, I want to be there.

(Albert Camus, The Stranger, 1942)

There is nothing [either] good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space.

(Shakespeare, Hamlet, c. 1600)

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

(W. B. Yeats, ‘He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven’, from The Wind Among the Reeds, 1899)

I have to remind myself to breathe—almost to remind my heart to beat!

I’m now quite cured of seeking pleasure in society, be it country or town. A sensible man ought to find sufficient company in himself.

(Emily Bronte, Wuthering Heights, 1847)

King as thou art, free speech at least is mine.

To make reply; in this I am thy peer.

(Sophocles, Oedipus Rex, c. 429 BCE)

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

(T.S. Eliot, from “Little Gidding,” Four Quartets, 1943)

It takes something more than intelligence to act intelligently.

I know that you don’t believe it, but indeed, life will bring you through. You will live it down in time. What you need now is fresh air, fresh air, fresh air!

It would be interesting to know what it is men are most afraid of.

(Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment, 1866)

References:

Neville, Thelma (1974), ‘Settlers’ Commemoration’, South African Panorama, October, 19 (10): 10-15.

— (1991), More Lasting than Bronze: A story of the 1820 Settlers National Monument, Pietermaritzburg: Natal Witness Printing and Publishing.

Ramaswamy, Sumathi (2023), ‘A Historian among the Goddesses of Modern India‘, How Secular is Art?, eds. Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Vazira Zamindar, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.