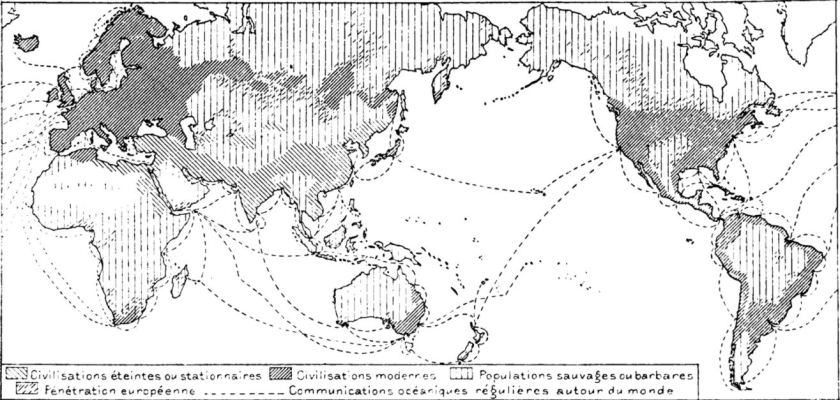

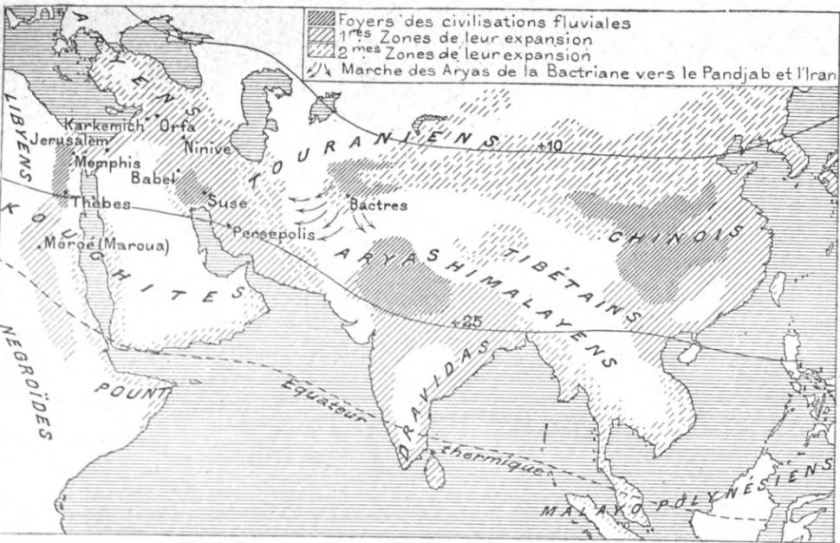

The following maps and images come from the largely forgotten works of two anarchist geographers of the late-nineteenth century: Léon Metchnikoff and Élisée Reclus. Like many leading anarchists of the period, they rejected political versions of geography based on the Westphalian model of state sovereignty that privileged land and territory and fetishized human difference in the nationalist and colonialist terms that became increasingly dominant over the course of the nineteenth century. Instead, in a move that was at once historical and geographical, they looked back to the longer, transcontinental history of civilizations (not nation-states), focusing on their interdependency (in trade, culture, language, etc.) and on the role rivers and oceans played in their formation and evolution. Without denying the violent realities of state-making whether ancient or modern—or what Metchnikoff called ‘the madness, hypocrisy and criminality’ of human history (1)—the new, anti-statist form of human geography they developed underpinned an alternative political vision based on the principles of freedom, co-operation and voluntary, non-hierarchical networks of association—for a detailed account of this political and scholarly conjunction, see Philippe Pelletier, Geographie & Anarchie (Éditions du Monde libertaire, 2013), and for a reaffirmation of the tradition, see Simon Springer, ‘Anarchism! What Geography still ought to be‘, Antipode, 44.5 (2012) and James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (Yale, 2009), especially Chapter 2 which considers the part rivers played in the formation of ancient states.

The following maps and images come from the largely forgotten works of two anarchist geographers of the late-nineteenth century: Léon Metchnikoff and Élisée Reclus. Like many leading anarchists of the period, they rejected political versions of geography based on the Westphalian model of state sovereignty that privileged land and territory and fetishized human difference in the nationalist and colonialist terms that became increasingly dominant over the course of the nineteenth century. Instead, in a move that was at once historical and geographical, they looked back to the longer, transcontinental history of civilizations (not nation-states), focusing on their interdependency (in trade, culture, language, etc.) and on the role rivers and oceans played in their formation and evolution. Without denying the violent realities of state-making whether ancient or modern—or what Metchnikoff called ‘the madness, hypocrisy and criminality’ of human history (1)—the new, anti-statist form of human geography they developed underpinned an alternative political vision based on the principles of freedom, co-operation and voluntary, non-hierarchical networks of association—for a detailed account of this political and scholarly conjunction, see Philippe Pelletier, Geographie & Anarchie (Éditions du Monde libertaire, 2013), and for a reaffirmation of the tradition, see Simon Springer, ‘Anarchism! What Geography still ought to be‘, Antipode, 44.5 (2012) and James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (Yale, 2009), especially Chapter 2 which considers the part rivers played in the formation of ancient states.

The first series of maps comes from Metchnikoff’s major work La civilisation et les grands fleuves historiques (Paris, 1889) from which Joyce borrowed in process of writing Finnegans Wake (see Chapter 3 of the book).

For the history of the earlier Apollo 8 (1968) ‘earthrise’ image, see here.