1. Have you ever met a tove? Or seen something that is a lighter shade of tove? Or witnessed someone tove with flair? Perhaps you have heard of a person called Michael Tove or, more plausibly, Birte Tove? Or read a novel in the Moomin series by Tove Jansson or seen Tove (2020), the movie about her life? Or bought a designer outfit from Tove Studio? Then again, is this tove as in love (tuv or /tʌv/ in IPA), grove (tohv or /təʊv/), or move (toov or /tuːv/)? Pronouncing the Scandinavian name is a bit easier: Tove, thought to be derived from Tófa, a legendary woman in an Old Norse saga, is rendered as ‘tu:ve’ in IPA (roughly toova). The London-based fashion house claims ‘TOVE is borne from the girl’s name originating from Denmark. It stands for strength and beauty, perfectly encapsulating everything that TOVE epitomises.’

2. If you stumble across Lewis Carroll’s ‘Jabberwocky’ on the internet—say, on the Poetry Foundation website, Google’s top-ranked search result—then you can settle one issue with some confidence. In the initial sentence of the poem, which runs across the first two lines, the word ‘toves’ functions syntactically as a regular noun, taking, for English, the standard plural form -s. So you could potentially encounter some toves, identifying them by the attributes and habits Carroll gives them: they are ‘slithy’ (adjective), they ‘gyre’ and ‘gimble’ (verbs), actions they seem to enjoy performing when it is ‘brillig’ (noun? adjective?), and they inhabit ‘the wabe’ (definite article+noun). This makes them likely to be an organic life-form, but are they plants, animals, viruses, something else? Reading the free-floating internet-version of the poem leaves the pronunciation problem unsolved as well. All we know is that ‘toves’ rhymes (imperfectly) with ‘borogoves’ (-guvs? -gohvs? -goovs?, and is this a hard and k-like /g/ or soft and j-like /dʒ/?).

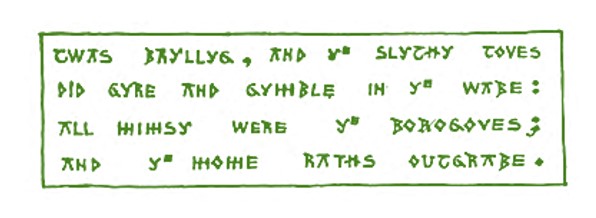

3. Reduced to a simple statement—‘The slithy toves gyre and gimble in the wabe’—Carroll’s initial sentence, the first version of which was a parody of Anglo-Saxon poetry he wrote in 1855 aged 23 (see above and below), anticipates the nonce-formulations beloved of early 20th-century philosophers. Andrew Ingraham, the American educationalist and accomplished philosophical dabbler, produced ‘The gostak distims the doshes’ (p. 154) in 1903, and Rudolf Carnap, the leading logical positivist and member of the Vienna Circle, followed with ‘Piroten karulieren elatisch’ in 1934 (trans. ‘Pirots karulize elatically’, p. 2). The philosophical concerns underlying these two sentences were different. Ingraham worried about language’s seductive power to make us ‘go on, not employing words to stand for things, or to call up thoughts in our minds, but to replace things, to be substitutes for thought’ (154). By contrast, Carnap wanted to show that, ‘given an appropriate rule’, all ‘word-languages’ (including Esperanto) can for all their many ‘deficiencies’ be formalized independently of ‘the meaning of words’, ultimately making the kind of ‘logical syntax’ he advocated possible (2). That Carroll’s pseudo-sensical but logically and grammatically acceptable jabberwocky sentence toys with both possibilities was no doubt not lost on the Oxford logician-mathematician Charles Dodgson.

3.1 Bertrand Russell and Noam Chomsky went on to develop Carnap’s thoughts about the promise of formalization in their own ways, using standard (if sometimes obscure) English rather than jabberwocky-words. Russell proposed ‘quadruplicity drinks procrastination’ in 1940 to show that ‘no ordinary language contains syntactical rules forbidding the construction of nonsensical sentences’ (166). Seventeen years later, Chomsky, inspired in part by Carnap, offered ‘Colourless green ideas sleep furiously’ and ‘Furiously sleep ideas green colourless’ to prove (as he thought) ‘the independence of grammar’ from semantics (and pragmatics): both sentences are ‘equally nonsensical’, he claimed, but ‘any speaker of English will recognize that only the former is grammatical’ (15). Chomsky also thought the sentences made ‘any statistical model of grammaticalness’ doubtful (16). While both are improbable, he believed English speakers would read the first with ‘a normal sentence intonation’ (not as separate words), recall it more easily, and learn it more quickly (16). Recent developments in neuroscience and AI (think ChatGPT) raise new questions about Chomsky’s doubts regarding statistical models of language learning.

4. Encountering ‘Jabberwocky’ not as a free-floating poem but as an integral part of Through the Looking-Glass (1871) is a very different experience. For one thing, when we first see it in Chapter 1 we look through Alice’s 7½ year-old eyes—worth noting she is at a key stage in her development as a reader, no longer a novice but not yet a fluent comprehender. Though she quickly cracks the mirror ‘code’ in which the poem is written—through the looking-glass toves reads sevot—she ends up grasping only a rough sense of the basic narrative: ‘Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I don’t exactly know what they are! However, somebody killed something: that’s clear, at any rate—’. She returns to the poem in Chapter 6, now as a perplexed reader seeking enlightenment from Humpty Dumpty. Besides being a riddle (answer: egg) borrowed from an eighteenth-century nursery rhyme, Humpty Dumpty is the mirror-world’s most surreal logician, chief grammarian, and its most imperious literary critic. ‘I can explain all the poems that were ever invented’, he tells Alice with characteristic bravado when she brings up ‘Jabberwocky’, ‘and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet.’

5. Humpty Dumpty glosses particular words from the first verse, revisiting the mock-philological explanations Carroll added to the original 1855 version (see below). Some are informatively and plausibly linguistic: ‘slithy’, for instance, is a ‘portmanteau’ made of ‘lithe and slimy’ (both of Germanic origin). Others are patently guesswork, even though they highlight some of the odd gaps between spoken vs. written English, as in ‘mome’ which is allegedly short for ‘from home’ (again both Germanic). In many cases, however, Humpty Dumpty simply resorts to stipulative definition, re-affirming his megaegomaniacal philosophy of language (Carroll’s satirical (self)portrait of Charles Dodgson?). So ‘toves,’ who ‘make nests under sundials’ and ‘live on cheese,’ are, according to the learned critic, ‘something like badgers—they’re something like lizards—and they’re something like corkscrews.’ John Tenniel, Carroll’s ingenious British illustrator, went with this, permanently fixing Humpty Dumpty’s stipulative image of the toves as strange, post-Darwinian hybrids (they were just a species of badger in Carroll’s original gloss). That still left the problem of pronunciation, at least until Carroll issued instructions in the preface to The Hunting of the Snark (1876): ‘“toves” is pronounced so as to rhyme with “groves’” (so tohvs or /təʊvs/), he insisted with Humpty-ish assurance. The preface also endorses his notorious ego-egg’s idea of the portmanteau.

6. James Joyce gave Humpty Dumpty a new life in Finnegans Wake (1939), in part, and characteristically, as a series of fragmentary letter-strings, ranging from the ‘humptyhillhead of humself’ (3) on the first page to ‘Humps, when you hised us and dumps, when you doused us!’ (624) four pages from the end. Humpty is also central to the spoof ‘Ballad of Persse O’Reilly’ (45-47) and a cryptic part of the seventh ‘thunderword’:

Bothallchoractorschumminaroundgansumuminarumdrumstrumtruminahumptadumpwaultopoofoolooderamaunsturnup! (314)

Yet it was Carroll’s particular take on the nursery-rhyme figure that proved most influential for Joyce. Carroll’s HD is one of many avatars of the masculinist, master-building HCE-figure and an archetype of the Wake’s large cast of absurdly scholastic male critics who, in one way or another, claim they can ‘explain all the poems that were ever invented’. These include the ‘grave Brofèsor’ (124), an aggressively pedantic palaeographer; Shaun, in his guise as a fundamentalist interpreter of ‘the authordux Book of Lief’ (425); and the ‘grisly old Sykos who have done our unsmiling bit on ‘alices, when they were yung and easily freudened’ (115). Joyce’s point? Following Carroll, he recognised that the fate of all these would-be, Humpty-ish language-masters is always sealed. Given the protean, endlessly rule-changing, and radically open character of living languages in all their spoken and written forms, they and all their scholastic kind are bound to have a great fall, particularly when they sit on disciplinary walls.

Postscript: Joyce did not target only professors, critics, linguists, and philosophers. He had so-called ‘ordinary readers’ in his sights as well. The ‘grave Brofèsor’, for instance, has a rhyming, non-identical twin in the ‘ornery josser’ (18), another bad male reader (see the ‘What is creative criticism?‘ post). So, for Joyce, distinctions like the one John Guillory draws in Professing Criticism (2022) between ‘lay’ and ‘professional’ readers are too assured (320). As Guillory notes, this binary deformed literary criticism from its very beginnings as an academic discipline. When it ‘crystallized in its present form in the twentieth century, its professionalized reading practice was defined precisely by a deliberate cultivation of a difference from lay reading and even by the expression of antagonism toward that mode of reading’ (327). To overcome the ‘spectacular failure’ of their own discipline, professionalized, university-based literary critics could do well to revitalize their subject by putting it on a new footing, Guillory suggests, this time acknowledging ‘the continuity between lay and professional reading’ (342). Yet with regret—‘alas’ he laments airily—he has ‘no program for reconciling these practices’ (342). Given the less promising, Humpty-Dumpty-like continuities between ‘lay’ and ‘professional’ male readers Joyce identified, it would be worth thinking twice before embarking on any such programme.

References:

Rudolf Carnap, The Logical Syntax of Language (1934; trans. 1937)

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass (1871)

——-, The Hunting of the Snark (1876)

——-, The Rectory Umbrella and Mischmasch (1932, see below)

Noam Chomsky, Syntactic Structures (1957)

Andrew Ingraham, The Swain School Lectures (1903)

James Joyce, Finnegans Wake (1939)

Bertrand Russell, An Enquiry into Meaning and Truth (1940)