Xu Zhimu’s poem ‘康桥西野暮色’ (‘Wild West Cambridge at Dusk’, 1922) is among the earliest literary responses to James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). As the award-winning translator Stuart Lyons explains in the note below, the 25-year-old Xu read Joyce’s new work in the spring of 1922 when he was studying at Cambridge University. Ulysses had only just appeared in book form: the first edition was published in Paris on 2 February, Joyce’s 40th birthday. Xu was particularly struck by its final section: Molly Bloom’s almost unpunctuated, eight-sentence, 62-page interior monologue (aka ‘Penelope‘).

Given the subject of his own poem, Xu may have had the closing turn of her nocturnal thought-drift in mind. Recalling Leopold Bloom’s proposal of marriage — it is 1904 and she is thinking back to 1888 — Molly relives the sensual memories that flooded the erotic intimacy of the moment, most of which centre on the time she spent in Gibraltar as a young girl. She remembers it as a place with ‘glorious sunsets’. These memories of memories form a vital part of her secret inner life which remains hidden from Bloom — they also inspired Kate Bush’s 1989 song ‘The Sensual World‘, retitled ‘Flower of the Mountain‘ in 2011.

I was thinking of so many things he didnt know of Mulvey and Mr Stanhope and Hester and father and old captain Groves and the sailors playing all birds fly and I say stoop and washing up dishes they called it on the pier and the sentry in front of the governors house with the thing round his white helmet poor devil half roasted and the Spanish girls laughing in their shawls and their tall combs and the auctions in the morning the Greeks and the jews and the Arabs and the devil knows who else from all the ends of Europe and Duke street and the fowl market all clucking outside Larby Sharons and the poor donkeys slipping half asleep and the vague fellows in the cloaks asleep in the shade on the steps and the big wheels of the carts of the bulls and the old castle thousands of years old yes and those handsome Moors all in white and turbans like kings asking you to sit down in their little bit of a shop and Ronda with the old windows of the posadas glancing eyes a lattice hid for her lover to kiss the iron and the wineshops half open at night and the castanets and the night we missed the boat at Algeciras the watchman going about serene with his lamp and O that awful deepdown torrent O and the sea the sea crimson sometimes like fire and the glorious sunsets and the figtrees in the Alameda gardens yes and all the queer little streets and the pink and blue and yellow houses and the rosegardens and the jessamine and geraniums and cactuses and Gibraltar as a girl where I was a Flower of the mountain yes

Stuart Lyons’s English rendering of Xu Zhimu’s poem was awarded first place (open category) in the Stephen Spender Prize 2020 for poetry in translation. I am grateful to him for allowing me to reproduce it and his accompanying note here. For more see Xu Zhimu in Cambridge — life and poetry (2021) and Lyons’s illustrated presentation (2021).

Among the other fruits of Xu’s year in Cambridge is the ‘Friendship/Handscroll’ (see below) for which he solicited contributions during his second visit to England in 1925. Contributors included the Chinese artist Zhang Daqian, the Chinese poet and artist Wen Yidou, the English artist Roger Fry, and the English feminist and socialist campaigner Dora Russell.

Xu has a further connection to this site because he admired and corresponded with Rabindranath Tagore, hosting him when he visited China in 1924 and 1929. Shortly before his death in 1941, Tagore wrote the following poem about his first visit, which speaks to the sentiments underlying the ‘Friendship Scroll’, to the intercultural ideals Tagore drew from the Baul tradition (see Chapter 4 of the book and the Fifth Proposition), and perhaps even to the inspiration Xu found in Joyce. Tagore’s conception of the ordinarily hidden ‘inner man [or self]’ certainly invites comparison with Joyce’s in Ulysses. It is poem #30 in the Bangla collection Janmadine (On My Birthday, 1941). The translation comes from Nirupama Rao’s Foreword to Tagore and China (2011). Tagore recalls the occasion, during his 1924 visit, when the leading Chinese intellectual Liang Qichao gave him the name ‘Zhu Zhendan’.

In the vessel of my birthdays

Sacred waters from many pilgrimages

Have I gathered, this I remember.Once I went to the land of China,

Those whom I had not met

Put the mark of friendship on my forehead,

Calling me their own.The garb of a stranger slipped from me unknowing,

The inner man appeared who is eternal,

Revealing a joyous relationship, unforeseen.A Chinese name I took, dressed in Chinese clothes.

This I know in my mind:

Wherever I find my friend, there I am born anew.

Life’s wonder he brings.

Note

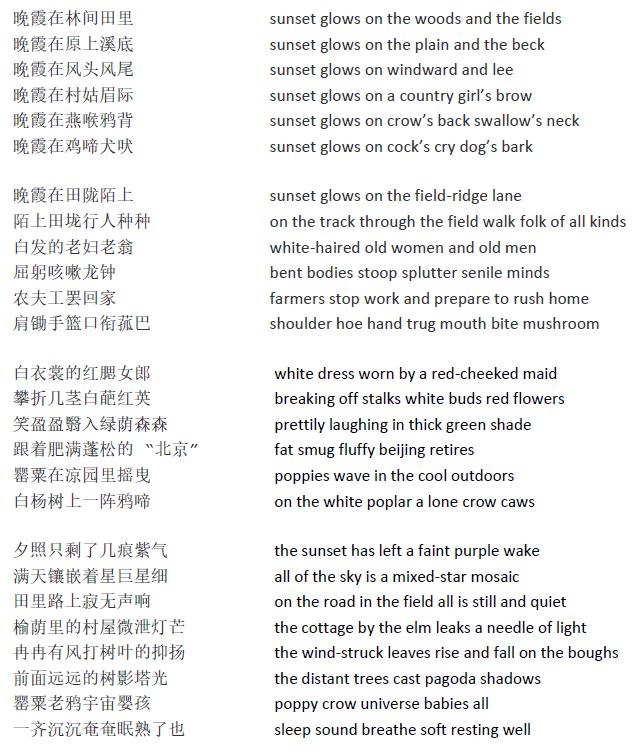

In the spring of 1922, Xu Zhimo read James Joyce’s newly published novel Ulysses. He was bowled over by Molly’s punctuation-free monologue in the final chapter. ‘Wild West Cambridge at Dusk’, depicting scenes around his home village of Sawston, was the result. When Xu sent it for publication, he included an introductory note. ‘A snake does not need feet in order to move,’ he wrote, ‘and a poem does not need punctuation.’ In Ulysses, he noted, there were ‘no capital letters, no ‘ ……? : —- ; —- ! ( ) “ ” but a cascade of truly great writing.’

I treated the exclamation mark in the standard Chinese text (stanza three, line six) and the inverted commas around 可可 (stanza two, line six) and 北京 (stanza six, line four) as probable interpolations and removed them from my English translation. Xu overcomes the need for punctuation through the clarity of his poetic writing. Every stanza describes an acutely observed phase of the closing day. His lines have colour, texture, sound and wit – ‘beijing’ refers to his pregnant wife.

Xu’s sometimes unusual choice of Chinese characters adds to the enchantment; he uses duplicated characters frequently and on occasion innovatively, a feature which I referenced through alliteration and assonance. I tried to respect Xu’s rhythmic and rhyming schemes and to be true to his imagery, while using vocabulary that was close to the Chinese but would strike a chord with English readers, for example in the star’s boat-ride across the clouds. In the last stanza, I aimed to express the scene though Xu’s eyes – the night sky as a mosaic, the needle of light from a darkened cottage and the pagoda-shaped shadows from the trees. ‘Wild West Cambridge at Dusk’ broke new ground. It is rhythmically compelling and artistically spectacular.

©Stuart Lyons 2020. All rights reserved.

‘Friendship/Handscroll/友谊手卷‘