1. Ludwig Wittgenstein used his own schematic version of Joseph Jastrow’s duck-rabbit figure in ‘Philosophy of Psychology — A Fragment’, a draft addendum to his Philosophical Investigations (1953), to clarify what he meant by “noticing an aspect.” He began with a more straightforward example: “I contemplate a face, and then suddenly notice its likeness to another. I see that it has not changed; and yet I see it differently” (§113). The duck-rabbit illusion added a further dimension by obliging him to “distinguish between the ‘continuous seeing’ of an aspect and an aspect’s ‘lighting up’.” (I am using Schulte’s revised translation of ‘Aufleuchten’, which Anscombe originally rendered as ‘dawning’.)

1.1 Writing as a philosopher, or, more accurately, as the philosopher’s anti-philosopher, Wittgenstein was not especially interested in the neuroscience of all this, though he recognized that “its causes are of interest to psychologists” (§114). Jastrow, who was a psychologist, did not go into any detail about the neural workings of the illusion either. The image is just one of many he used to illustrate his central thesis about the creativity of human vision in ‘The Mind’s Eye‘, an article he wrote for the general readership of Popular Science Monthly in 1899:

It is a commonplace taught from nursery to university that we see with our eyes, hear with our ears, and feel with the fingers. This is the truth, but not the whole truth. Indispensable as are the sense organs in gaining an acquaintance with the world in which we live, yet they alone do not determine how extensive or how accurate that acquaintance shall be. There is a mind behind the eye and the ear and the finger tips which guides them in gathering information, and gives value and order to the exercise of the senses. This is particularly true of vision, the most intellectual of all the senses, the one in which mere acuteness of the sense organ counts least and the training in observation counts most.

Though Jastrow took his own duck-rabbit image from Harper’s Magazine, it first appeared in Fliegende Blätter, a German weekly, in 1892. For an animated version of this kind of perceptual illusion, using puppetry, see Stephen Mottram’s stunning ‘The Parachute‘ (2016); and this 1971 film about the related work of the Swedish psychologist Gunnar Johansson.

1.2 This section of ‘Philosophy of Psychology — A Fragment’ revisits §5.5423 of the Tractatus (1922):

2. The strange phenomenon of “noticing an aspect” was, for Wittgenstein, essentially a philosophical matter relevant, in the first instance, to epistemology. “The importance of this is the difference of category between the two ‘objects’ of sight” (§111), he commented, before adding “we are interested in the concept and its place among the concepts of experience” (§115). The challenge, in other words, was to construe the difference and relationship between the face seen directly (but still as a face), and the same face seen in the light of a particular likeness; or, by analogy, the same drawn lines (as visual marks) seen as a rabbit and as a duck–in the latter case, we can’t put the same visual cues in the same category simultaneously. (This relates to Wittgenstein’s broader interest in, and concept of, ‘family resemblance‘ and to his claim ‘meaning is a physiognomy‘.) To put it in Jastrow’s terms, we could say the first ‘object’ is seen with the physical eye, the second created by the ‘mind’s eye’. For contemporary neuroscientists, as for Wittgenstein, it would be more plausible to say that the bio-cultural brain, which learns instinctively from experience and through specific training, generates both, producing the rich visual world of ordinary ducks and rabbits (and their representations) as well as the peculiarities of the duck-rabbit illusion — the latter in fact shows the extraordinary, albeit automatized, creativity involved in ‘seeing things’, whether that means recognizing faces as such (Wittgenstein’s ‘continuous seeing’), a vital imperative for newborns, or seeing likenesses between them (Wittgenstein’s ‘lighting up’) — see also the phenomenon of pareidolia (seeing faces in things) and the neuroscience behind it.

3. The philosophical ramifications of this are beyond the scope of this post. What is relevant here are the connections underlying Wittgenstein’s preoccupation with the modalities of visual perception and his interest in writing and reading. These emerge explicitly in another section of the ‘Fragment’:

In German, the reversed, handwritten word is ‘Freude’. Wittgenstein focuses on the contrast between the way we see the word and the image, in effect noticing different aspects in each case. We judge the writing aesthetically, for instance, and relate it to our motor skills as practised writers. Again, he simply raises the issue of perceptual difference, steering clear of causal explanations — for contemporary neuroscientists (see Dehaene and Wolf) the learned automaticity of reading, the abstractive power of the brain and its deep interconnectedness go a long way towards such an explanation.

3.1 Wittgenstein invites us to compare his example of mirror-writing to one in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Towards the end of the first chapter, in a bid to escape her disturbing conversation with the White King and Queen, the first mirror-world figures she meets, Alice picks up a book, only to encounter another puzzle:

At first she thinks it is “some language I don’t know” — crucially, for Wittgenstein, she still sees this as language, not as a series of visual marks, since this is already part of her learned, perceptual repertoire (‘continuous seeing’). But then, in a ‘lighting up’ moment, a “bright thought” strikes her: “Why, it’s a Looking-glass book, of course! And if I hold it up to a glass, the words will all go the right way again.” She then reads “Jabberwocky” in the mirror, only to find herself at a loss once again. “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I don’t exactly know what they are!”, she says, “However, somebody killed something: that’s clear, at any rate—.”

4. Wittgenstein would have appreciated Alice’s new sense of befuddlement. His own extended reflections on reading in the Philosophical Investigations itself (sections §156-78) include the following passage:

Confusingly, Anscombe turned Wittgenstein’s original line of asemic manuscript squiggles (‘arbitrary flourishes’, he calls them) into the following sequence of typographically familiar, non-phonetic symbols, some of which are both utterable and meaningful:

For the everyday duck-rabbit illusions of writing in English, think only of the way we can’t see the letters ‘s’, ‘t’, ‘o’, and ‘p’ and the word ‘stop‘ at the same time, or the way we can see the configuration Reading at the beginning of a sentence as the activity (pronounced reeding) and as the place name (pronounced reding) but not as both at once. Like Lewis Carroll and James Joyce (see the ‘Strip Teasy’ post), Wittgenstein took nothing for granted when it comes to the peculiarities of the literate brain or the many ways of seeing and knowing it affords.

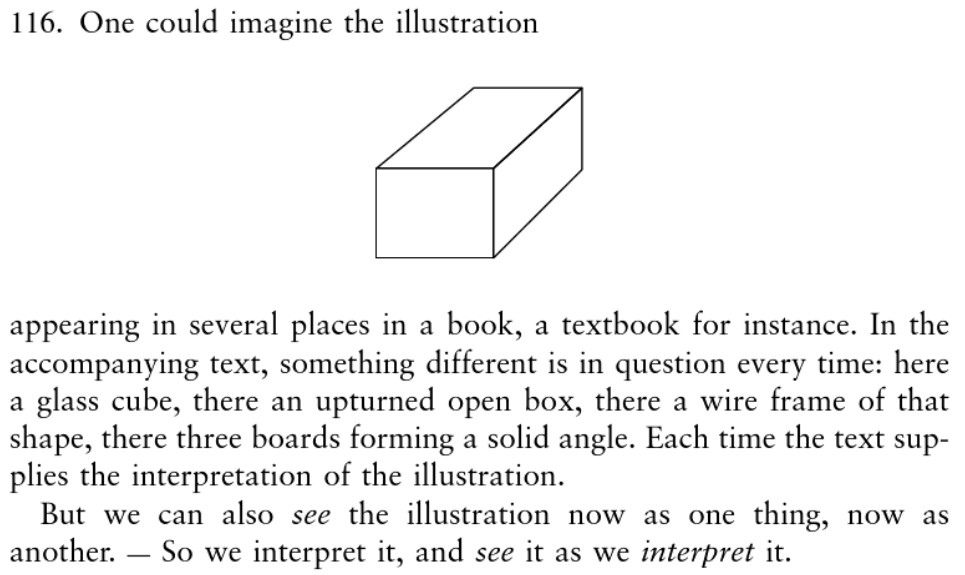

5. Section §169 (above) of the Investigations focuses on the puzzles of the grapheme-phoneme connection, but, returning to the ‘Fragment’, we can see that Wittgenstein’s interest in the modalities of visual perception relates to his concerns about semantics as well. To illustrate another, again slightly different, form of aspectual seeing, he offered this example:

For Wittgenstein, we experience the specific meaning of an individual word, whether heard as a phoneme or read as a grapheme, in a comparably shifting, highly contextualized way — the word now taking the place of the cube/box/etc. “You can say the word ‘march’ to yourself,” he notes later in the ‘Fragment’, “and mean it at one time as an imperative, at another as the name of a month. And now say ‘March!’ — and then ‘March no further!’ — Does the same experience accompany the word both times — are you sure?’ (§271). Earlier, via another example of cryptic inscription in the ‘Fragment’, he made the connection to how we experience meaning as we read too: