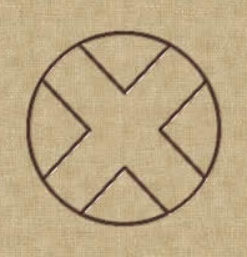

1. This is the ancient Egyptian hieroglyph niwt (pronounced ‘nee-oot’), one of the earliest known written inscriptions meaning ‘city’ or ‘town’. As the economic historian Robert S. Lopez (1910-86) intimated in his 1966 essay ‘The Crossroads within the Wall‘, it is also an apt symbol for the intricacies of what it might mean to think interculturally.

The cross represents the convergence of roads which bring in and redistribute men, merchandise, and ideas. This convergence entails a quickening of communication which is nearly always a great advantage, but may become a handicap if speed grows so frantic that the city has no time to keep its share of the incoming goods and to impress its mark on the goods it re-exports. The circle, in the hieroglyph, indicates a moat or wall. This need not be materially erected so long as it is morally present, to keep the citizens together, sheltered from the cold, wide world, conscious of belonging to a unique team, proud of being different from the open country and germane to one another. The wall, too, may become an obstacle if it is too high and tight, if it hinders further growth, above all if it frustrates the opportunity for exchanges beyond it. (27)

‘Communication plus togetherness,’ Lopez continues, ‘or, a special aptitude for change combined with a peculiar feeling of identity: is this not the essence of the city?’ Lopez’s astutely balanced analysis has a particular pertinence to ancient city-states, which are also intimately associated with the origins of writing (see the ‘Scott’s paradox’ post). It could just as well be applied, figuratively if not literally, to the modern nation-state, whether in its older, Europeanized monolingual, monocultural forms, or its newer, post-European multilingual, multicultural iterations. In each case, the double-edged symbolism of the circle and the cross points to the promise and the perils of belonging and interconnection, identity and change. The need to juggle these competing imperatives is, as I argue in the book, central to Joyce and Tagore’s thinking about language, culture, community, state-making and more.

2. A. K. Ramanujan (1929-93), the great Indian poet and scholar, quotes Lopez in his 1970 essay ‘Towards an Anthology of City Images‘, which is, among other things, a powerful defence of literary thinking — Ramanujan is especially interested in literature’s potential as a complement to the positivistic forms of thought that dominated the social sciences in the first half of the 20th century. After citing the descriptions of two cities, modeled on the ancient port of Pugaar (Pukar) and the inland capital Madurai (Maturai), in the Tamil epic Silappatikāram (c. 5th century CE), he comments: ‘Pukar is pre-eminently the Crossroads City and Maturai, the Walled City.’ Yet the epic does more than weigh the costs and benefits of these two contrasting cityscapes. For Ramanujan, it shows the classical poet’s ‘intuitive grasp of a typology of cities’ as well as a ‘grasp of structural relations and their entailments in the details of experience’, which is ‘worth the social scientists’ attention.’ The reason? ‘The poet’s detail not only offers realisations and intuitions of structure, but a whole repertory of hypotheses that might be the beginnings of fresh scientific observations’ (69).

3. Much the same could be said of the way Joyce imagines the Dublin of Finnegans Wake (1939) neither as an idealized city on the hill in the Platonic/Christian tradition, nor as one of the many fallen cities of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), but as an ever-changing intersection of two world-historical forces, each potentially creative and destructive: a free-flowing, circulatory ‘feminine’ force, associated chiefly with the river Liffey and Anna Livia Plurabelle (ALP); and a master-building, rising-and-falling (tumescent-detumescent?) ‘masculine’ one, linked primarily to the port city of Dublin itself and Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker (HCE) — see the history of the phrase ‘beyond the pale‘. Tagore applied his version of this doubling vision to India as a whole, or, rather, to the free, independent future India he dreamt in Gitanjali (1910), where he wrote (in Ketaki Dyson’s English translation): ‘We shall give and receive, mingle and harmonise: / there’s no turning back / on this seashore of India’s grand concourse of humankind’ (151). Again, as with Joyce and the ancient Egyptian scribes, the crossroads, or crosscurrents, are as necessary, and potentially as dangerous, as the containing circle or wall.

Fantastic – enjoyed it thoroughly – while teaching basic semiotics to Management & Marketing 1st years here in dusty potholed Mahikeng in RSA!