Anselm Kiefer’s exhibition at the White Cube Gallery in London (June-August 2023) is an engaging multimedia homage to James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939). (Kiefer is a painter and sculptor, born in Germany in 1945.) The exhibition is arranged across four rooms linked via a large central passage, so five gallery spaces in all. Each invokes a different aspect of Joyce’s Wake, combining key motifs, suggestive interpretations, and multiple cross-references.

The entrance

The entrance

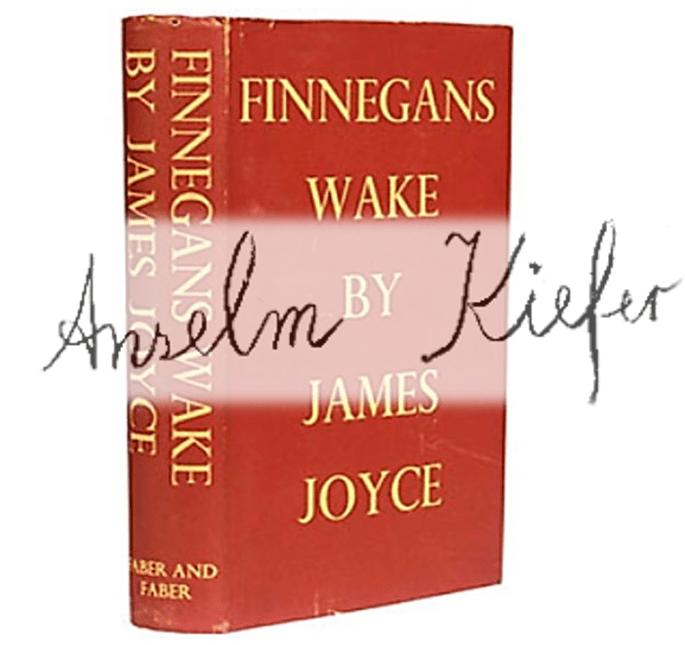

You enter the main passage through a gap in the hanging, film-like strips of a curtain, which recalls the ‘photoist’s’ chemically deformed horse photograph, a ‘grotesquely distorted macromass of all sorts of horsehappy values and masses of meltwhile horse’, itself an emblem of the Wake’s guiding preoccupation with the many technologies and modalities of representation (FW, 111). The most pronounced of these in the exhibition is Joyce’s own medium, writing itself, which features throughout, whether as graffiti on the walls, as captions for the displays, as inscriptions in the paintings, or as marks on assorted detritus. These are all rendered in script rather than print form.

The dark passage and the light side room

The curtained entrance leads directly into the long, connecting passage, which is dimly lit and lined on both sides with floor-to-ceiling shelves, all displaying an array of cultural artefacts, natural specimens, and more. It is a cabinet of dark curiosities, a playful invocation of a Joycean/Wakean unconscious, and a material recreation of the ‘Willingdone Museyroom’ with which the Wake begins (8). Among the many items on display are skeletons, dried plants, a DNA helix, metal tools, rusted machinery, a hanging wardrobe, pornographic images, political symbols (notably the hammer and sickle), a model of a cathedral, a rusted bicycle, printers’ trays, books, etc. The temptation to see this as a version of the unconscious is reinforced by the smallest side room, the second of three leading off to the left of the passage. Like the passage, this is set out as a multi-shelved Museyroom, sometimes repeating items in its darker twin, though now brightly lit and often white — in effect, the space of the conscious self. These connections with difference creatively complicate the standard reading of the Wake as Joyce’s book of the night, in contrast to Ulysses (1922), his book of a day. They also productively undercut the inevitable spatializing effects of the exhibition itself, revealing that in Kiefer’s Wake, as in Joyce’s, no binaries are safe.

The heap and heliot room

The first of the rooms leading off to the left is dominated by a heap of sand in which discarded shopping trolleys, inscriptions, rusty sunflowers, and a wheelchair are variously buried. This recalls the ‘fatal midden’ in which ‘the original hen’ finds the manuscript of ALP’s unreadable letter (110). One of the walls includes a group of graffitied citations addressing political and economic issues: ‘making a venture out of the murder of investment’ (341), ‘marx my word fort’ (83), ‘our bourse and politicoecomedy are in safe with good Jock [Jet] Shepherd’ (540). The only painting, which covers one of the larger walls, depicts a dark, massed crowd looking at a bright, visionary light, invoking the flower-like ancient Irish ‘heliots’ who, following St Patrick, turn to worship ‘the firethere the sun in his halo cast’ (612-13).

The HCE room

The third and final room leading off to the left of the dark passage is dedicated to HCE, the Wake’s ‘male’ (tumescent-detumescent) principle, who is associated with master-builders of various kinds, the rise and fall of leaders, states, empires, etc. Like the first room, it is dominated by a central heap, though this is now a rubble of concrete slabs (the Berlin Wall?), barbed wire, and some sunflower-like forms. The room has three large, dark paintings: a portrait of HCE’s family (ALP, Shaun, Shem, and Issy), a tribute to oil painting (‘and oil paint use a pumme if yell trace,’ 230), and a war-ravaged field of flowers, recalling the quotation from Edgar Quinet’s Introduction à la Philosophie de l’Histoire de l’Humanité (1825) that Joyce reworked throughout the Wake. The quotation, which Joyce cites in full only once and in French, translates as follows:

Today, as in the time of Pliny and Columella, the hyacinth disports in Gaul, the periwinkle in Illyria, the daisy on the ruins of Numantia; and while around them the cities have changed masters and names, while some have ceased to exist, while the civilisations have collided with one another and smashed, their peaceful generations have passed through the ages and have come up to us, fresh and laughing as on the days of battles. (281)

The ALP room

The only room leading off to the right of the dark passage is a counter space dedicated to ALP, the Wake’s ‘female’ (Anna Livia Plurabelle) principle, who is associated with the river Liffey, all forms and varieties of fluid connection, and the Wake itself as a never-ending, free-flowing stream of letters. Uniquely, all four walls have paintings, a series of eleven, all featuring the same striking mix of browns, greens, copper blue, and luminous gold. The link to writing and the Wake is established via the scattered piles of water-weathered, lead-paged books in the middle, a material contrast to the concrete rubble of the HCE room. A rusty scythe amid the books hints at the ALP death monologue with which the Wake ends without ending.