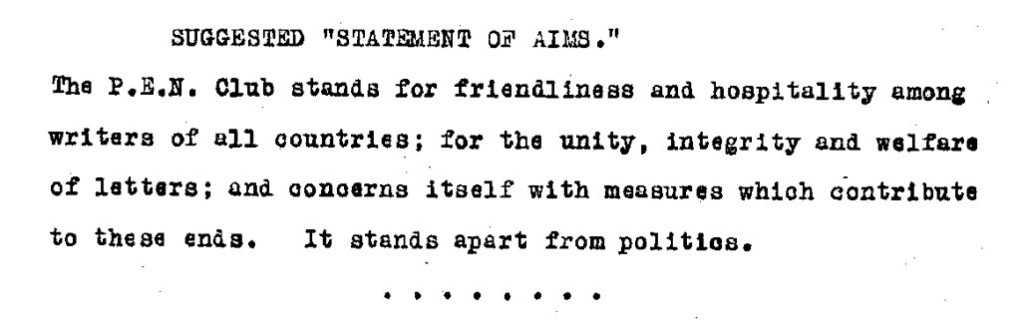

1. The text above comes from the minutes of a meeting held by the founding centre of the international writers’ group PEN in London on 5 October 1926. It is essentially a draft of what would become PEN’s original ‘Statement of Aims’, the final wording of which was collectively agreed the following year. This statement, in turn, formed the basis of what would become the ‘PEN Charter’ in 1948 (see ‘Shadows and Ghosts: The Evolution of the PEN Charter‘).

2. There are several ways to think about the wording of this document. You could, for instance, begin by seeing it simply as a strategic move in the debates PEN was at the time having with itself as a relatively new organisation. From the start, its inaugural president, the English writer John Galsworthy, was insistent about keeping PEN apart from, perhaps above, the increasingly polarized politics of the immediate post-war years. ‘It meddles not with politics,’ he wrote in a letter to the London Times on the eve of PEN’s first international congress in April 1923. Three years later, he had reasons for wanting to reaffirm this commitment. At the congress held in Berlin in May 1926, he had been challenged by a group of young German writers of the left—the so-called ‘Gruppe 1925’, which included Bertolt Brecht, Robert Musil, and Ernst Toller—who considered PEN’s stance on politics outdated and naïve at best, irresponsible at worst. The draft statement was Galsworthy’s response.

3. Yet it was not just a rallying call designed to bolster internal support for the kind of literary activism the London centre believed PEN should represent. By adding the disclaimer about politics, the draft statement took a position in a wider contemporary debate about writers and their public role. For one thing, it allied PEN to champions of an autonomous ‘Republic of Letters’ like Julien Benda, whose polemic against intellectual partisanship La Trahison des Clercs appeared in 1927. For another, the disclaimer linked PEN to the International Committee on Intellectual Co-Operation, the precursor to UNESCO within the League of Nations, which was founded in 1922. Despite its role as an advisory body to the League, the ICIC, like PEN, saw itself as an international association of non-aligned clercs in Benda’s sense. Its founding members included Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Paul Valery, and Gilbert Murray, many of whom had close ties to PEN (see Artefacts of Writing, Chap. 1).

4. As the ‘Gruppe 1925’ showed, it is not difficult to critique this non- or anti-political position. Brecht and his co-members thought it damned PEN as an establishment dining club. Today we might be more inclined to focus on what it reveals about early PEN’s parochialism not just as a largely Anglo-European affair but as a coterie of clercs who had no qualms about appointing themselves guardians of the universal—Benda’s eternal ideals of justice, truth, and beauty. ‘We writers are in some sort trustees for human nature,’ Galsworthy declared, toasting PEN’s inauguration in 1921. As it happens, it was not long before events caught up with him. At the Dubrovnik congress, just over a decade later, members of the newly Nazified German PEN tried to save themselves from censure by invoking Galsworthy’s humanistic ideals, showing how amenable his strictures against political meddling were to political meddling. The strategy failed. PEN took a stand against Nazism and, for the first but not the last time in its history, it expelled one of its own centres. ‘After 1933’, as the international secretary Hermon Ould later put it, ‘the International PEN and a Totalitarian form of government were shown to be incompatible.’ Does this mean PEN’s early efforts to stand ‘apart from politics’ were fatally undermined? Flash forward to Exhibit B, which comes from PEN International’s current website.

5. The key detail here is the apparently unremarkable wording about its charitable status: ‘International PEN is a registered charity in England and Wales with registration number 1117088.’ To appreciate the significance of this you need to search gov.uk’s official Register of Charities where you can learn two things. The first is that PEN International was incorporated as a charity under the law of England and Wales only in 2006. The second is that it defines its primary object as a charity in the following elaborate terms:

To promote human rights (as set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) and subsequent United Nations conventions and declarations and in regional codes of human rights which incorporate the rights contained in the UDHR and those subsequent conventions and declarations) throughout the world.

Its second and only other charitable object is ‘to advance the understanding, appreciation and development of the creative art of writing.’

6. So far, perhaps still so unremarkable. At this point, however, it is worth recalling that, until the changes introduced under the Charities Act (2006), human rights organisations were officially barred from charitable status under English law because they were deemed to be political. This changed with the passing of the Human Rights Act (1998), which laid the foundations for a new statutory understanding of such organisations—in effect making the promotion of human rights a legitimate ‘charitable purpose’ in the eyes of the state. Determining exactly what this means, especially for an organisation like PEN, is not straightforward, since, as the Charity Commission specifies in one of many guidelines on this necessarily vexed issue, ‘the purposes of a charity must be clear, unambiguous and exclusively charitable,’ or, more bluntly, ‘an organisation will not be charitable if its purposes are political.’ In another document, the Commission explains that ‘political purpose’ means ‘any purpose directed at furthering the interests of any political party; or securing, or opposing, any change in the law or the policy or decisions of central government, local authorities or other public bodies, whether in this country or abroad.’

7. And yet, ever since its founding in 1921, even under Galsworthy’s presidency, PEN has been campaigning on behalf of writers against any number of abuses, whether by state or non-state actors, ranging from specific acts of persecution and censorship to policies on free expression and linguistic rights. So how can it be ‘a registered charity in England and Wales’? Again, the Charity Commission’s guidelines provide some intricate pointers.

Whilst a charity cannot have political activity as a purpose, the range of charitable purposes under which an organisation can register as a charity means that, inevitably, there are some purposes (such as the promotion of human rights) which are more likely than others to lead trustees to want to engage in campaigning and political activity.

So, PEN can campaign to change laws, policies, and political decisions, since that is a legitimate ‘activity’, not an illegitimate ‘purpose’. In another, arguably more intricate formulation, the guidelines accept that promoting human rights is at best ‘analogous’ to ‘existing charitable purposes’, rather than charitable per se. ‘Given that respect for human rights is widely regarded as a moral imperative’, the Commission notes, ‘the well-established charitable purpose of promoting the moral and spiritual welfare and improvement of the community provide a sufficient (but not the only) analogy for treating the promotion of human rights generally as charitable.’ In these variously subtle senses, then, PEN still ‘stands apart from politics.’

8. Why bring these two exhibits and historical moments together? Not to claim that PEN’s early position on politics prefigures the strange convolutions of English charity law in the twenty-first century. Rather, tracing the genealogies of thought and action connecting early PEN’s efforts to create space for itself and for literature outside politics with the terms in which human rights are conceptualized today, reveals something about the history of literary activism over the past century, and perhaps something about its future too.

For more on the history of PEN, see PEN: An Illustrated History (2021), and the Writers and Free Expression project.

For more on the fate of the UK Human Rights Act, see Merris Amos, Why UK approach to replacing the Human Rights Act is just as worrying as the replacement itself, 23 June 2022.