‘And this also has been a dark place.’

1. These words are spoken by Joseph Banda (b.1998) in the final chapter of Namwali Serpell’s novel The Old Drift (2019). He is sitting on board the Vulture, a fishing boat, anchored on Lake Kariba, the vast dam bordering Zambia and Zimbabwe, and he is speaking to his half-brother Jacob, Naila (Joseph’s girlfriend), and Mai, the owner of the boat. It is 2023 and revolution is in the air: the four are poised to sabotage the dam’s hydroelectric power plant as part of a project to resist the increasingly oppressive incursions of the modern surveillance state. Explaining his gnomic statement, Joseph continues:

I was thinking of the olden days, when the British first came here, a hundred years ago. Imagine the feelings of a local chief — what is the Tonga word? — a muunzi, chased suddenly to the north; run over the land across the region in a hurry and put in charge of one of these settlements that the white men — a lot of useless men they must have been, too — had built for 60,000 villagers in a month or two. It must have seemed like the end of the world. (p. 547)

Joseph has two colonial-era cataclysms in mind: the establishment of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) as a British protectorate in 1924, and the construction of the Kariba Dam thirty years later, which forced the resettlement of around 60,000 Tonga people. As a writer, Serpell is doing something else with his monologue. By having her fictional creation speak these words in particular, she is creatively disrupting the literary inheritances of the colonial era, using this brief scene on the Vulture to re-write the opening of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899).

2. In Conrad’s story, it is Marlow, the English seaman, who says: ‘And this also has been one of the dark places of the earth.’ He not only uses a slightly different syntax and lexicon — he doesn’t mean what Joseph means by ‘dark’, for instance — he also invokes a different history. He goes on to imagine the Roman conquest of darkest Britain ‘nineteen hundred years ago—the other day.’ Moreover, Marlow is on board the Nellie, a ‘cruising yawl’ anchored on the Thames, and, unlike Joseph, he is speaking to four middle-class white men, all pillars of the British empire. Serpell’s young, revolutionary quartet are, by contrast, diverse in more ways than one: Joseph and Jacob are of mixed British and Zambian heritage, Naila is Italian-Indian, and Mai, the boat owner, is Chinese. Reflecting other political and economic times, Conrad’s boat owner is an English ‘Director of Companies’ — think Cecil John Rhodes whose British South Africa Company controlled Northern Rhodesia from 1895 to 1923.

3. The Old Drift does not just tamper creatively and critically with Heart of Darkness in this one short scene. It opens up a new way of reading what has long been one of Conrad’s most contentious works. The reason for this is, on the face of it, surprising because it concerns the seemingly technical question of literary genre. At the most overt level, Serpell’s novel is a family chronicle tracing the tangled colonial and postcolonial histories of three families across three generations from the 1870s to the 2020s. The main narrative is divided into sections called ‘The Grandmothers’, ‘The Mothers’, ‘The Children’ — the last tells the interwoven stories of Joseph, Jacob, and Naila. Yet, at another, more covert level, The Old Drift is an ingenious work of science fiction — and so a worthy winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award 2020. This is not so much because it includes a jocoserious tale about an earlier generation of visionary revolutionaries who plan to send a Zambian to the moon. It is because the five main parts of the narrative are regularly interspersed with italicized passages of poetic prose in which a chorus-like swarm of mosquitoes comment on the chaotic course of human history — at least so it seems, until the very end when the mosquitoes morph into something rather different. Not to give away too much: in their new, non-insect guise they play a vital role in the Vulture-four’s ultimately calamitous plot to sabotage the Kariba Dam. As this last dramatic act shows, and as the mosquitoes buzzingly narrate throughout, the old drift is really history itself, especially as seen through the genre of the family chronicle: a sometimes violent, occasionally absurd catalogue of errors, accidents, mutations, and unintended consequences, driven as much by large juggernaut forces (like colonialism and malaria) as by the minute butterfly (mosquito?) effects of chance and wayward desire.

4. This innovative feature of The Old Drift brings the less obvious generic complexity of Heart of Darkness more clearly into view — though, in this comparison, Conrad’s novella emerges not as a successful fusion of science fiction and family chronicle, but as a fraught, even fatal, blend of science fiction and quasi-realist political satire. The easiest way to get a handle on this is via the figure of Marlow who is, in reality, at least two Marlows: let’s call them Marlow and Marlow.

4.1 Marlow is the sardonic teller of the political satire who sees through the lies and folly of empire, unlike his listeners on board the Nellie or the credulous and corrupted fellow-colonists he encountered on his journey into the heart of Africa in the narrative past. ‘The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much’, he tells his listeners early on. And when his aunt repeats ‘all that humbug’ about the European civilizing mission — again like many others, including his listeners — he ‘ventured to hint that the Company was run for profit.’ This Marlow is also outraged by the violence and suffering he witnesses. ‘They were not enemies, they were not criminals, they were nothing earthly now’, he remarks of one brutalized African group he met, ‘nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation.’ In the face of all this, he pinned all his hopes at the start of his journey on a meeting with Kurtz, only to have them shattered when he discovers that Kurtz is the rapacious monstrosity of empire writ large. In keeping with the coded conventions of some political satire, Marlow never names the river he journeys up to find Kurtz — like he never identifies Brussels, where the unnamed ‘Company’ for which he works has its headquarters, calling it only ‘the sepulchral city’ — but he moves in a recognizably realistic world, occasionally mentioning actual west African towns by name: Grand Bassam (Ivory Coast), for instance, and Little Popo (Aného in Togo).

4.2 Marlow inhabits a very different genre. Unlike Marlow, who travels up river in a ‘tin-pot steamboat’, for instance, he appears to be in something more like H.G. Wells’s time-machine (The Time Machine, 1895) — again there is a difference, however: unlike Wells’s time-traveller, who journeys into the distant future, Marlow voyages into the remote evolutionary past, back to the origin of the species. ‘We were wanderers on a prehistoric earth,’ he now tells his listeners, ‘on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet.’ (Characteristically, Marlow uses the inclusive first-person plural to talk about the fellow travellers his satirical namesake disdains.) And now, the Marlow who has previously borne witness to the dehumanized African victims of empire, says this:

But suddenly, as we struggled round a bend, there would be a glimpse of rush walls, of peaked grass-roofs, a burst of yells, a whirl of black limbs, a mass of hands clapping of feet stamping, of bodies swaying, of eyes rolling, under the droop of heavy and motionless foliage. The steamer toiled along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy. The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us—who could tell? We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. We could not understand because we were too far and could not remember because we were travelling in the night of first ages, of those ages that are gone, leaving hardly a sign—and no memories.

Marlow differs in two other key respects as well. Unlike Marlow, the outraged satirist who exposes Kurtz as the ultimate sham, a monster posing as a philanthropist, the time-travelling Marlow sees him as a visionary who can stare into the amoral, evolutionary origins of homo sapiens — prehistory’s conscienceless, nihilistic darkness — and pass judgement. Of Kurtz’s notoriously enigmatic deathbed pronouncement, Marlow says: ‘He had summed up—he had judged. ‘The horror!’ He was a remarkable man.’ And, finally, unlike Marlow, who says he ‘can’t bear a lie’, Marlow ends his sci-fi travelogue by recounting the lie he tells Kurtz’s ‘Intended’ on his return to ‘the sepulchral city,’ an act of deliberate concealment that suppresses the truth of empire and the truth of human origins in a single gesture. The reason? As Marlow (and no doubt Marlow) tells his listeners — in a final moment of dubious male bonding — she is, as a woman, not capable of bearing much reality. ‘I could not tell her’, he says, ‘It would have been too dark—too dark altogether….’

5. Heart of Darkness exerted a considerable influence over the course of the twentieth century. As a political satire, it became a reference point for the international human rights campaign against what E.D. Morel called The Congo Slave State (1903) — King Leopold II’s brutal and, at first, privately owned, African fiefdom — and decades later it provided the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola’s indictment of the Vietnam War, Apocalypse Now (1979). It was no less influential as a sci-fi journey back to the origins of the species: in this guise it left its mark on, among others, T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf — the former in The Waste Land (1922), ‘The Hollow Men‘ (1925), and Four Quartets (1935-42); the latter from her debut The Voyage Out (1915) to her last novel Between the Acts (1941). The trouble is Conrad’s novella is not an anti-imperial satire plus a post-Darwinian sci-fi travelogue. It is both at once, a combination which, as Chinua Achebe argued in the 1970s, has fatal consequences for its handling of race. For Achebe, the issue is not just that Marlow sees the indigenous Africans of the 1890s as emblems of ‘prehistoric man’ but that Marlow-Marlow is a fictive mask for Conrad’s and Europe’s racist image of Africa. What a comparison with The Old Drift reveals is that Conrad’s trouble with race may have as much to do with Heart of Darkness’s generic complexity as with anything else. Unlike Serpell, who uses the mosquitoes’ science fiction chorus to comment philosophically and poetically on the family chronicle, Conrad stitches Marlow’s Wellsian travelogue into Marlow’s political satire, confounding any ethical insight either story might afford on its own terms and exposing the essential incoherence of his own novella.

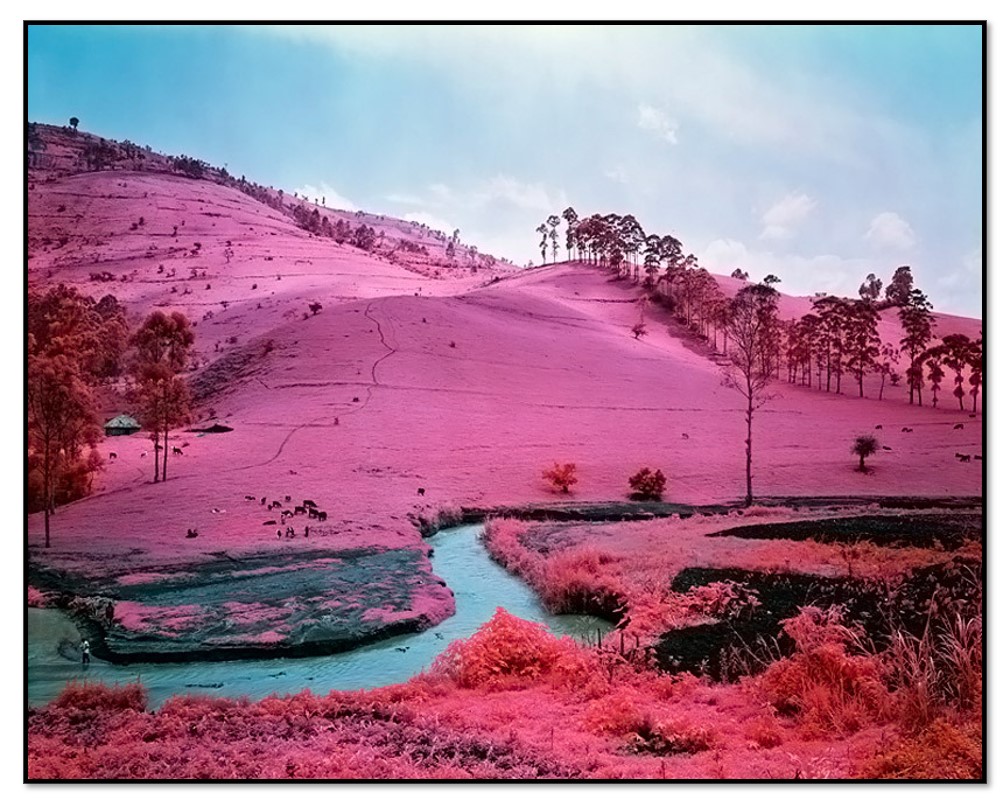

6. Understood in these terms, and taking a cue from The Old Drift’s preoccupation with modern surveillance technologies, Heart of Darkness invites comparison with Richard Mosse’s Infra (2012), a photographic project in which Mosse, an Irish visual-conceptual artist, used infra-red film to document guerrilla conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Yet, once again, there is a difference. Mosse chose Kodak’s Aerochrome film knowingly, fully aware of its origins as a military surveillance technology used to detect targets for aerial bombing. This deliberate choice has consequences for him as a photographer. It also has consequences for viewers of his photographs who cannot but ask uncomfortable questions about themselves and the medium through which they ‘see’ his surreal Congo. Mosse’s related project Incoming (2017) has a similarly disturbing effect. It is difficult to imagine Conrad being as aware of the compromised, self-cancelling generic technologies he chose to tell his fictionalized story of another Congo journey more than a century ago. What is clear is that Heart of Darkness puts contemporary readers in as challengingly complicit a position as Infra’s contemporary viewers.