Ɔːl kʌltʃəz ɛgzɪst ɪntəkʌltʃəli.

Ĉuij kulturoj ekzistas inter’kulture.

Is idir-cultúrtha a mhaireann gach cultúr.

Zonke iinkcubeko zalamene.

所有文化都以跨文化的方式存在.

جميع الثقافات هي عبارة عن تفاعلات ثقافية

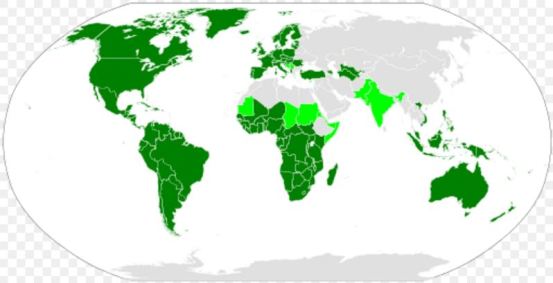

1.1 These sentences represent six attempts at translating the English sentence ‘All cultures exist interculturally’, beginning with the International Phonetic Alphabet, then Esperanto, Irish Gaelic, isiXhosa, Chinese (traditional) and Arabic. A seventh attempt, in Bengali or Bangla, is used as a header for this site. Five of the natural languages in this group are among the top ten most spoken languages in the world: Chinese (in all spoken forms) is ranked first with 1,302 million first-language speakers (as of October 2016), English is third with 329 million, Arabic is fourth with 267 million, and Bengali is seventh with 189 million. On current estimates there are 8.1 million isiXhosa speakers in South Africa and 138,000 Irish Gaelic speakers in Ireland (around 1.1 million across the world). It is often claimed that around 2 million people speak Esperanto as an additional language. All these figures are, of course, debatable and much debated. Where these languages appear on the Wikipedia rankings by articles, tells a different story with particular relevance to the question of knowledge creation and the digital revolution today: English comes top by a very long way (with over 5.6 million), Chinese is 14th (just over 1 million), Arabic is 19th (just over half a million), Esperanto is 31st (247,000), Bengali is 72nd (almost 59,000), Irish Gaelic is 79th (just over 47,000), and isiXhosa is 240th (736).

1.2 Before considering the translations as such, it is worth noting that five out of the eight versions of the sentence are represented in what is now generally called the Latin alphabet and the Roman script. This simple detail betrays a complex history. Stories of empire, first Roman, then British or European, and Christian evangelism lie behind the written versions of English, Gaelic, and isiXhosa; while a shorter but no less tangled history of European dominance, especially in the fields of writing and internationalism, lies behind the IPA and Esperanto. The Arabic, Bengali and the Chinese alone represent the many other writing systems in use around the world.

1.3 It is perhaps unsurprising that the translations into IPA and Esperanto are among the most straightforward. As a constructed or auxiliary international language, Esperanto was designed to be very close to most European languages, including English. This reflected its primary purpose which was to serve as a linguistic antidote to the poisonous national and ethnolinguistic rivalries that began to take hold across Europe in the late nineteenth century. And in the case of IPA what we have is less a translation than a transcription into a relatively neutral system of sound notation that is nonetheless deeply embedded in the Latin alphabet and Roman script. The precise form of the transcription will, of course, differ depending on the accent of the speaker. In this version the sounding of ‘cultures’, for instance, appears in its common British form with the initial ‘u’ emerging from the back of the mouth; in American English it is often pronounced with the ‘u’ further forward, giving ‘kəltʃəz’, not ‘kʌltʃəz’.

1.3.1 Once we turn to the five natural languages things get more complicated, as the back-translations show. In the case of Irish Gaelic and Bengali, the differences appear at first to be merely syntactic.

Irish Gaelic: ‘It is interculturally that every culture exists/lives/survives.’

Bengali: ‘All cultures do indeed live/survive interculturally.’

Even here, however, there are uncertainties about the most appropriate verb choice, some differences in emphasis, and, as we’ll see later, some inescapable challenges when it comes to the substantive concept ‘culture’.

1.3.2 In the case of Chinese, isiXhosa and Arabic, the variances are more pronounced, partly because it is all but impossible to capture the deliberately reflexive use of the adverbial form in the English. Central to the English formulation is the idea that while we often talk about cultures as if they are readily identifiable and countable things, like certain species of plant or animal, the fact that they are, like shifting sandbanks, always exposed to unpredictable and potentially transformative cross-currents makes any such identifications at best provisional (see Third, Fourth and Fifth Propositions).

Chinese: ‘All cultures exist in a cross-culture mode.’

isiXhosa: ‘All cultures are related to each other.’

Arabic: ‘All cultures are expressions of cultural interactions.’

Here the general idea of the interrelationship among cultures comes across, but the point about their mode of existence, as labile objects of thought and feeling that are never fully graspable, is lost. In isiXhosa and Chinese it is as if the presumed separateness of cultures, as seemingly bounded, countable things, is linguistically inescapable. This presumption is, of course, also generally there in the ordinary English usage of the word ‘culture’ on its own. In Arabic, the difficulties turn, in part, on the grammatical untranslatability of the verb ‘exist’, though the adverb is also far from straightforward. In the sentence, which romanizes roughly as Jami’ al-thaqafat hiya ‘ibara ‘an tafa’ulat thaqafiya, the penultimate word (tafa’ulat), meaning ‘interactions’, is something like an adverbial noun which is modified by the adjective ‘cultural’ (thaqafiya).

1.4 In 2016 the online Oxford English Dictionary identified fifteen uses of the word ‘culture’ as a noun, ranging from ‘the practice of cultivating the soil’ to ‘the attitudes of an organization’. For the purposes of the discussion on this site, two can be singled out: ‘culture’ as ‘the arts and other manifestations of human intellectual achievement regarded collectively’ (OED, sense 6); and ‘culture’ as ‘the distinctive ideas, customs, social behaviour, products, or way of life of a particular nation, society, people, or period’ (OED, sense 7a). It is primarily in this second sense that ‘cultures’ could be said to ‘exist interculturally’. Think of the intricate lines of affiliation between two otherwise seemingly distinct national cultures (the US and the UK, say), or of the ways in which the erudite male English elite identified with ancient Greece in the nineteenth century (see Fifth Proposition). Yet it is also ‘culture’ in the sense of the arts and other ‘human intellectual achievements’ that ‘exists interculturally’, as ideas, artefacts, and practices, like letter- or character-forms, words and phrases, move across borders and take up a new life in new contexts.

1.4.1 As the translations above show, it is possible to find workable equivalents for culture in the sense of a ‘way of life’ in Gaelic (cultúr), isiXhosa (inkcubeko), Chinese (文化, wénhuà in Pinyin), Arabic (الثقافات), and Bengali (সংস্কৃতি). The fact that many of these counterparts are, like the English culture, linked via etymology, extension or other associations to an underlying idea of cultivation, implying not just a transformation or refinement of something deemed natural, raw, coarse or crude but the ideals of a relatively settled agrarian polity, hints at a deeper level of connection—for more on the part these lexical associations have played in the history of state-making, see James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed (2009), especially pp. 26-32. The Bengali word, for instance, which has its origins in the verb ‘to cultivate’, is a figurative extension of the noun meaning ‘a refined, reformed, or corrected state’. Sounded out phonetically—roughly shawngshkriti in the romanized form—it is possible to hear the link to the word Sanskrit (literally ‘refined speech’), the ancient Indo-Aryan language of learning, religion and high culture (often contrasted to Prakrit, literally ‘vernacular’ or ‘ordinary speech’). Developing a similar line of thought, the isiXhosa word is derived from the verb chubeka which means figuratively ‘to know how to behave appropriately’. The root word in this case is chuba which means ‘to peel away,’ as in ‘peel away the husk from the corn or maize cob’, hence, figuratively, ‘to sort the good from the bad, or the valuable from the worthless’, like the Christian biblical expression ‘to separate the wheat from the chaff’. ‘Refinement’ is also included among the many meanings of the Chinese character 文 (wén), again linking (archaic) literal ideas of agrarian cultivation to (modern) figurative ideas of manners, taste and customs; while the Arabic word ثقافة (thaqafa) is associated etymologically with ideas of trained excellence and discipline. The English poet and essaysist Matthew Arnold underscored these statist or communitarian associations in Culture and Anarchy (1869), arguing that ‘culture indefatigably tries, not to make what each raw person might like, the rule by which he fashions himself; but to draw ever nearer to a sense of what is indeed beautiful, graceful, and becoming, and to get the raw person to like that’ (64). In many languages, then, the equivalent of the word culture, understood as a ‘way of life’, points to the distinctive ways in which particular (settled, agrarian) polities act on raw materials (nature, experience, the individual, etc.), refining them and in the process creating value. Seen in this context, the claim ‘All cultures exist interculturally’ implies that this distinctiveness is, in part, fashioned through endless borrowings and reworkings from other cultures (for more on this see the ‘Scott’s Paradox’ post).

1.4.2 Inevitably, however, some things get ‘lost in translation’ or, more accurately, some aspects of the word or character do not make the transfer because they remain too deeply embedded in each language or writing system. While we often translate words and sentences successfully, we can’t, of course, do the same for whole systems and their complex histories, the boundaries of which are, in any case, far from clear. This is most obviously reflected in the fact that the use of culture and its equivalents has evolved differently across languages. We have already seen that it has over the centuries acquired fifteen uses in English. In Chinese the character 文 on its own has almost a dozen primary meanings, ranging from ‘pattern, script or writing’ to ‘cover up or conceal’, and including ‘language’, ‘ritual’, and ‘literary composition’. (The same character also of course represents very different words and sounds, depending on the language: wén in Mandarin, bun in Japanese, and mun in Korean.) If we add its many possible pairings, as in文化 (wénhuà), the list of meanings extends considerably. Translation is also limited because words or characters often acquire particular overtones in the source language which, for historical and cultural reasons, their equivalents in the target language do not share. The long history of Irish resistance to English colonial dominance, for instance, lies behind the Gaelic phrase an cultúr (‘the culture’), meaning ‘the distinctive, even self-sufficient Gaelic way of life’.

1.4.3 In contrast to this, the English word, which is linguistically very close to the Gaelic, owes much to the German Kultur when used in this sense. The OED traces this particular meaning to the late-18th century and to the influence of the German philosopher J. G. Herder whose own thinking, it should be said, was influenced by the Scottish literary figures James Macpherson and Hugh Blair. This later German-derived meaning overlaid the earlier Anglo-Norman uses of the word (from the French culture, and the Latin cultura) which moved from meaning ‘farming’ or ‘husbandry’ in the 12th century (again note the agrarian connection) to the ‘development of language and literature’ in the 16th. Adding another layer of complexity, the OED notes that the late 18th-century usage acquired further overtones when paired with civilization. To talk about a ‘way of life’ as a culture after the 18th century was relatively neutral or descriptive, while to describe it as a civilization often implied a normative idea of progressive development or hierarchy. At the same time, Kultur acquired its own resonances in German, particularly in the writings of Fichte and Humboldt, where it was contrasted to Zivilisation (humane or enlightened order) and linked to Bildung (training or education). As I noted in Chapter 1 of the book, the latter had a particular influence on Matthew Arnold. Culture and Anarchy could more accurately be re-titled Bildung or Laissez-faire Liberalism, where the untranslated German term means state-sponsored education or intellectual formation in Humbolt’s sense – hence the importance Arnold attached to collective, and in his view objective, values when discussing the need for the ‘raw person’ to become an incorporated member of the community or state. I also discussed how the distinction between culture, specifically national culture, and civilization had an impact on the emergence of English studies in Oxford at the end of the nineteenth century, and on Rabindranath Tagore’s anti-nationalism in the 1920s and 1930s (see Third Proposition).

Acknowledgements:

For their translations of the English sentence and their detailed comments on the intricacies of the process, I am grateful to Ketaki Kushari Dyson, Bill Harris, Rana Issa, Russell Kaschula, Pam Maseko, Bernard O’Donoghue, Wang Weiping, and Zhu Feng.

For a related comment on the value of thinking interculturally, see Nicolas Geeraert, ‘How knowledge about different cultures is shaking the foundations of psychology‘, 9 March 2018.

References:

Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy, ed. Stefan Collini (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Joshua Howgego, ‘Britain’s oldest writing found buried near London Tube station‘, New Scientist, 1 June 2016.

OED Online. Oxford University Press, December 2015, http://www.oed.com/, accessed 3 August 2016.

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (New Haven: Yale, 2009).