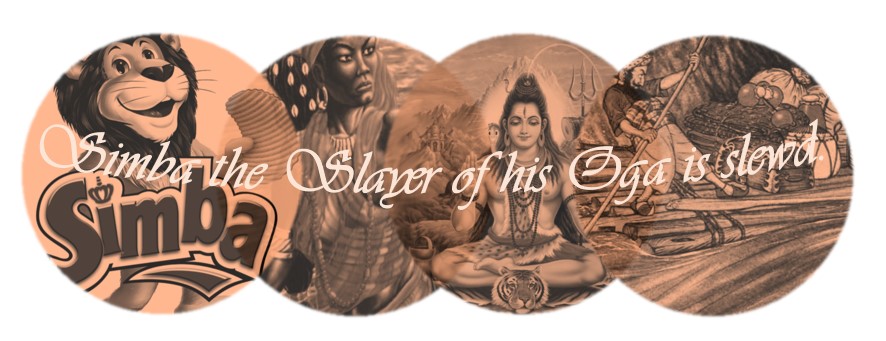

Maass! But the majik wavus has elfun anon meshes. And Simba the Slayer of his Oga is slewd. (203)

I recently ran a test with this quotation from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) using GPT-4, the latest iteration of OpenAI’s large language model. I first wanted to see how many languages it could identify in the word-string. It focused on the unconventional spellings of English words, adding only that ‘Simba is a Swahili word for ‘lion,’ and it’s also a well-known character from The Lion King‘, and that Oga seems to be ‘a term from African pidgin English.’ With some further prompting, it specified the meaning of oga as ‘boss’ or ‘leader’ in ‘Nigerian Pidgin’, which ‘has roots in English and local Nigerian languages, including Igbo, Yoruba, and Hausa.’ It missed the Swahili words ‘maji’ (water), ‘wavu’ (net), and ‘elfu’ (one thousand). It could also not identify any river names, any reference to Hindu myth (‘Shiva the Destroyer’), the Arabian Nights (‘Sinbad the sailor’), or, indeed, the source as Finnegans Wake. (For more on this particular Wake-string, see the Finnegans Wake/Nakshi Kantha post.)

I then asked it to produce a comparable string based on this example. This is what it came up with:

Ombra! In the dervish swirleth lies a tempo fable, entwining runes and riddles. So whispers Bantu the Weaver of her Saga, beguiled.

It also appended this explanatory note:

GPT-4: This example attempts to capture some of the characteristics of Joyce’s work:

- Language Blending: By combining English with words and influences from other languages, this text mirrors the multilingualism found in Finnegans Wake.

- Symbolism and Ambiguity: The passage is filled with suggestive imagery and symbols (such as “dervish,” “tempo,” and “Weaver”) that invite multiple interpretations, akin to Joyce’s layered meanings.

- Character Naming: “Bantu the Weaver” could be seen as a parallel to “Simba the Slayer,” a blending of real and mythological reference, and a fusion of different cultural influences.

- Literary Allusions: The passage may contain hidden or subtle references to various myths, histories, and literatures, mirroring Joyce’s densely allusive style.

It’s worth noting that replicating Joyce’s unique style fully is a considerable challenge, given the depth, complexity, and idiosyncrasy of his writing in Finnegans Wake. However, this example may convey some of the novel’s flavor and approach to language.

I then initiated the following, Turing-like exchange:

PMcD: Isn’t ‘Bantu’ a controversial word?

GPT-4: Yes, the term “Bantu” can indeed be viewed as complex and controversial, depending on its usage and context.

Historically, “Bantu” refers to a group of over 500 closely related languages spoken by various ethnic groups in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is also used to describe the people who speak these languages.

However, during the apartheid era in South Africa, the term was co-opted by the ruling government to categorize, segregate, and control people. The racial classification system that included the term “Bantu” was tied to deeply discriminatory practices. This association with apartheid has led to negative connotations and controversy around the use of the term in certain contexts.

In the context of literary or artistic expression, the use of such a term might be an intentional choice by an author to evoke specific cultural or historical meanings, themes, or emotions. However, its use can also be seen as insensitive or inappropriate, depending on the understanding, intent, and awareness of both the writer and the audience.

In the text I crafted, the intention was to emulate the linguistic blending and cultural fusion characteristic of Finnegans Wake. However, I acknowledge that the choice of the term “Bantu” might carry unintended connotations or sensitivities. In constructing literary texts, especially those that draw on real-world languages and cultural identifiers, awareness of historical and sociopolitical contexts is crucial, and careful consideration should be given to the potential impact and interpretation of specific terms and symbols.

PMcD: And doesn’t ‘deverish swirleth’ rehearse racist clichés?

GPT-4: You are quite correct to bring attention to these concerns. The term “dervish” refers to members of Muslim religious orders known for their practice of whirling dances as a form of physical meditation. It has been exoticized and stereotyped in various ways in Western literature and art. Coupling “dervish” with “swirleth” might inadvertently invoke Orientalist clichés, which often portray the Eastern world as mystical, irrational, and exotic.

The use of such language can perpetuate harmful stereotypes, especially when taken out of its cultural and historical context. Even when the intention is to emulate a certain style or artistic expression, such as the experimental language in Finnegans Wake, care must be taken not to reinforce or propagate stereotypes and biases.

Literary experimentation that draws on cultural symbols and terms can be a rich and nuanced form of expression, but it also carries the responsibility of understanding and respecting the complexity of the cultures being referenced. A more thoughtful and informed approach to these issues might include engaging with primary sources, consulting with cultural experts, or otherwise grounding the work in a genuine appreciation and understanding of the cultures being invoked.

Your observations are valuable reminders of the importance of sensitivity and critical awareness in literary and creative endeavors. Thank you for bringing these issues to the forefront.

PMcD: How do you explain your choice of these terms and references?

GPT-4: Your critique is well-received, and I must acknowledge that the choices made in crafting that text were flawed. My intention was to create a passage that echoed the complexity and multilingualism found in Finnegans Wake. However, I did not adequately consider the implications of certain terms and references.

- “Bantu”: The use of this term was an attempt to invoke a cultural element, but as you’ve pointed out, it’s a term fraught with historical and political sensitivity. My use of it was ill-considered.

- “dervish swirleth”: Again, the intention here was to create a sense of rhythm and mysticism associated with James Joyce’s writing style. However, the choice inadvertently played into Orientalist clichés.

I appreciate your bringing these concerns to my attention. It serves as a stark reminder that words and phrases cannot be used merely for their aesthetic or sonic qualities without considering their cultural, historical, and ethical dimensions.

PMcD: That is fine as a description of what you did, but it doesn’t explain why or how you arrived at the text you did? Try again, giving a real explanation.

GPT-4: Certainly, I appreciate your insistence on a more transparent and reflective explanation. Here’s a more detailed breakdown of how and why I arrived at the text in question:

- Emulating Joyce’s Style: My primary goal was to emulate the unique linguistic style found in Finnegans Wake. Joyce’s work often includes wordplay, multilingualism, and mythical allusions. I sought to mirror these elements, but without the deep contextual understanding that Joyce had.

- Choosing Multilingual Elements: In an attempt to replicate Joyce’s use of multiple languages, I included words like “Bantu” and phrases like “dervish swirleth.” However, I failed to appreciate the nuanced cultural and historical significance of these terms.

- Aesthetic and Sonic Appeal: The construction of the phrase “dervish swirleth” was partly guided by a desire to create a pleasing rhythm and imagery. This aesthetic-driven choice was made without sufficient consideration of the stereotyping and exoticization that it might entail.

- Lack of Critical Reflection: I did not critically assess the potential implications and sensitivities of the words and phrases chosen. This lack of reflection led to the inclusion of terms that might rehearse stereotypes or invoke controversy.

- Limitations of Quick Response: The creation of the text was done in the context of responding to a question in real-time, without the benefit of extended reflection or consultation with cultural or historical sources. While this doesn’t excuse the choices made, it does highlight the challenges of producing thoughtful and sensitive content in a rapid-response setting.

I hope this explanation provides a clearer understanding of how and why the text was constructed as it was, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to reflect on these important issues.

PMcD: Doesn’t the real explanation lie in the way you synthesize language based on your data sets, modelling, etc?

GPT-4: Yes, you are absolutely correct. The underlying mechanisms that led to the creation of the text can be traced back to the models and data sets on which I was trained. Let’s delve into that aspect:

- Training Data: I’ve been trained on a diverse range of texts, including literature, websites, and other written materials. The associations, words, and styles I draw from reflect the breadth and biases of this training data.

- Language Modeling: The way I synthesize language is guided by statistical patterns in the data on which I was trained. These patterns include both syntactic structures and semantic associations. The language used in the generated text was influenced by these underlying patterns.

- Limitations of Context: While I strive to generate contextually relevant and culturally sensitive text, the model doesn’t inherently “understand” cultural nuances or ethical considerations. Its responses are based on statistical relationships rather than a deep understanding of human culture and history.

- Emulating Style without Ethical Consideration: In trying to emulate Joyce’s style, the model drew upon linguistic elements that may resemble his work but without the nuanced ethical considerations that a human author might apply. This can lead to the inclusion of terms or phrases that are problematic or controversial.

- Lack of Introspection: Unlike human authors, the model doesn’t have personal intentions, beliefs, or a conscious thought process. It generates text based on learned patterns and algorithms, not personal reflection or deliberate choice.

Your question has brought to the forefront the intricate relationship between data, modeling, and the resulting generated text. It highlights the importance of considering not only the artistic or literary aspects of text generation but also the underlying technology, methodology, and ethical dimensions.

The incident illustrates how AI models, while powerful and versatile, must be used with awareness of their limitations and potential pitfalls, especially in complex and sensitive areas such as literature, culture, and ethics.