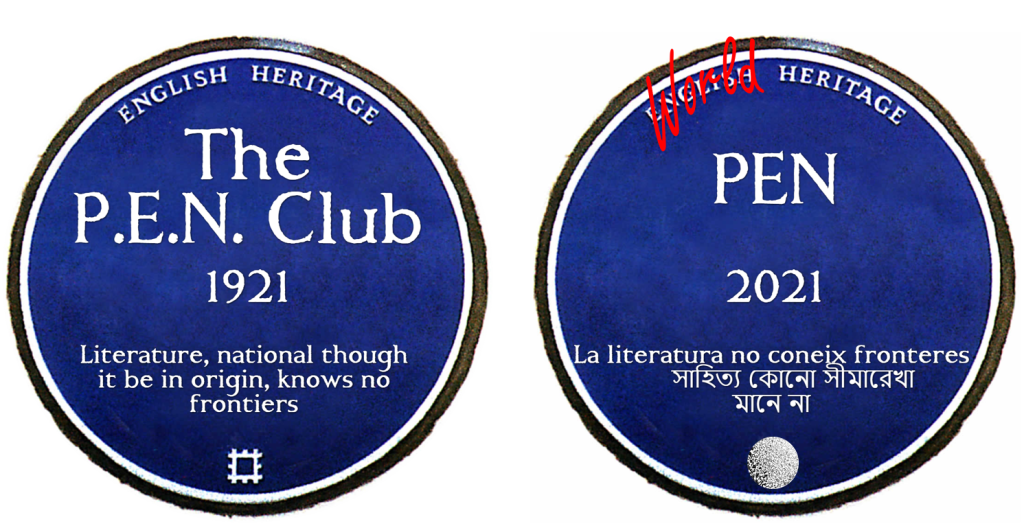

Literature, national though it be in origin, knows no frontiers, and should remain common currency between nations in spite of political or international upheavals.

1. This is the first article of the original statement of aims that PEN, the world’s largest and oldest association of writers, formally agreed in Brussels at its 5th international Congress in 1927. PEN was founded in London in 1921 and held its first official Congress there in 1923. Haunted by the horrors of the First World War, the statement is universalist in aspiration and anti-nationalist in spirit, though it presupposes the primacy of the nation at every point — not just in the sub-clause ‘national though it be in origin’ but in the phrase ‘between nations’. As this wording was preserved when the three-part statement became the four-part PEN Charter in 1948, it effectively stood as an emblem of PEN’s internationalist vision for just over seventy-five years.

1.1 The statement also reflected the ‘new idealism’ of PEN’s founding President, the British novelist John Galsworthy. ‘All works of the imagination’, Galsworthy wrote in an article on ‘International Thought’ for the London Times on 30 October 1923, ‘are the property of mankind at large’ and ‘any real work of art, however individual and racial in root and fibre, is impersonal and universal in its appeal.’ As I argue in the book, this kind of thinking, which combined the national and the universal, also underpinned the development of English as an academic subject in late-Victorian Oxford where Galsworthy studied law, graduating in 1889. Yet this was not simply a matter of literary aesthetics for Galsworthy. It concerned the writer’s special calling. At a time when governments, journalists, scientists and financiers continued to see themselves as ‘trustees for competitive sections of mankind’—again he had in mind the malign nationalism that led to the First World War—he argued writers had a ‘plain duty’ to be the heralds of a co-operative, law-based international order and the champions of ‘a new idealism.’ At the same time, Galsworthy always insisted on PEN being an association not an amalgamation of national centres.

2. Such at least was the vision. Not everyone agreed, even in the 1920s. Some doubted PEN could ever stand above, or even outside, politics and others worried that Galsworthy made it look too much like a literary rival to the League of Nations. And then reality got in the way. Since some languages do not have a localized territory or the backing of a state, alternative, culture-based centres were formed almost immediately, beginning in 1922 with the Catalans in Barcelona, followed a year later by the Spanish in Madrid. Scottish PEN was founded in 1927. Then there was the question of exiles (Russian and German in the first instance) and the tensions between the Flemish and the French in Belgium. The greatest challenge in the interwar years, however, came from Yiddish writers who found themselves adrift after the Polish centre in Warsaw turned down their request for co-membership. After much debate, the solution, formally accepted in 1927, was to establish a Yiddish centre in the contested city of Vilna (now Vilnius, capital of Lithuania) with further branches in New York and Warsaw. Two years later, at the 1929 Congress in Vienna, it was then agreed that ‘the method of dividing the P.E.N into sections and the right of voting at congresses should be based on literary and cultural’, rather than national grounds. Despite this, the first article of the Charter remained unchanged until 2003.

3. At the 67th international Congress, held in London in November 2001, the Canadian and German PEN centres initiated a discussion to revise the original wording. Reflecting some of the interwar concerns, the President of PEN Canada, the exiled Iranian writer Reza Baraheni, was among the leading proponents for change. They set out four main reasons for doing so.

a. [The original wording] had never been historically correct, and intrinsically excludes all literature written before the development of nation states.

b. erroneously accepts without question the late 18th-century proposition that literatures are “national”, a concept promoted by developing nation states in order to foster the citizens’ identification with the nation, and opposed even then by Goethe and others who believed in “world literature” and held that in an age of unlimited intellectual exchange literature belongs to the whole world.

c. totally neglects the post-colonial development in Africa and the Arab states, where literature is predominantly seen in a pan-African or pan-Arab context, and in the case of Africa is written in a wide variety of cross-border indigenous and colonial languages.

d. culturally marginalizes literature written by exiled, emigrated or migrant writers.

4. Following their interventions, the Canadian and German centres proposed a new formulation at the next Congress, held in Ohrid, Macedonia in September 2002:

Literature of whatever provenance or language is a world cultural heritage and must be protected and upheld at all times as the free and common currency of all people, particularly in periods of political or international upheaval.

This effectively removed the contentious phrasing about the ‘national’, though the sentence read like something composed by committee via email over some months, which is, in fact, how it emerged. Again, not everyone was happy. Writers from the former Soviet Union and Eastern bloc spoke against the change, describing what the almost talismanic 1948 Charter, which champions free expression, meant to them throughout the dark years of the Cold War. They also worried about the loss of the word ‘national’, which had acquired a new significance for them since 1989 and for everyone in the era of globalization. By contrast, African writers spoke for the proposal because they liked the word ‘protected’, which addressed concerns they had about marginalized languages and literatures.

5. For the English writer Victoria Glendinning and literary agent Susanna Nicklin, the problems were stylistic. Feeling that the new version was not ‘in keeping with the spare, clear wording of the Charter,’ they proposed an alternative, which involved subtracting rather than re-writing. This broke with protocol — according to PEN’s rules, you cannot amend an amendment in the course of discussion — but, characteristically, an unfussy solution was found: the English and Canadian delegates were sent away to re-draft the amendment, a task that took four hours. Why so long? Again characteristically, the debates reflected everything for which PEN stands—‘communication, tolerance, impassioned discussion, literary quotation, story-telling, poetic digressions, tales of wrongful imprisonment, life-stories’ and more, as Glendinning and Nicklin reported.

6. What resulted was a small but significant reformulation, which re-founded PEN as a truly supranational, non-statist world association, equal to the broader vision of ‘language communities’ articulated in the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights (1996), a document PEN did much to shape (see the ‘Linguistic Rights’ post):

Literature knows no frontiers, and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals.

The change in modal verb — ‘should’ to ‘must’ — also strengthened the organization’s commitment to its denationalized founding pledge, making the moral recommendation of the 1920s a mandatory obligation for the new millennium. The familiar but questionable metaphor ‘common currency’, which makes literature something like a cultural Euro or Eastern Caribbean dollar, remained unchanged. After two years of intense debate, the final wording was formally incorporated into the Charter when the amendment was ratified a year later at the 69th Congress in Mexico City, a meeting otherwise dominated by reports on the growing number of attacks on writers and journalists around the world—775 in 2003 alone.

See also ‘Shadows & Ghosts: The Evolution of the PEN Charter,’ Los Angeles Review of Books, 4 October 2021.

For more details on the 2002 PEN Congress in Macedonia, see Joanne Leedom-Ackerman’s blog post ‘PEN Journey 26: Macedonia—Old and New Millennium‘, 24 April 2020; and Victoria Glendinning and Susanna Nicklin, Boating for Beginners: 68th PEN International Congress, Ohrid, 17-24 September, 2002 (October 2002).