Colorless green ideas sleep furiously

1. Challenged to produce sentences similar to Noam Chomsky’s classic exemplar from Syntactic Structures (1957, p. 15), you, as a biocultural human intelligence, might follow a thought process something like this:

a. Select 5 familiar English words (i.e. nothing obscure, no pseudo words, no novel coinages, etc).

b. Choose words representing the same four parts of speech — adjective (2), noun, verb, and adverb — that can be used in a similarly structured grammatical sentence.

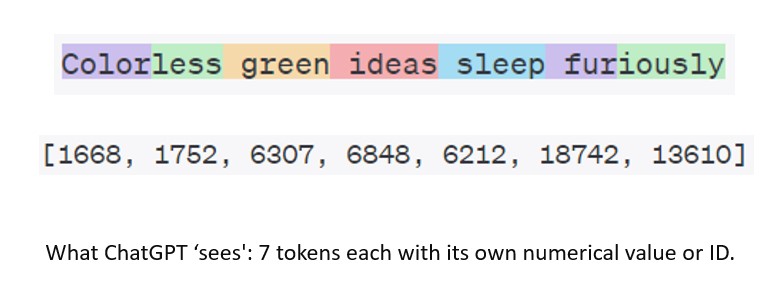

c. Ensure that the (semantic? logical?) relationships between the words are comparably odd (e.g. the two adjectives must contradict each other, the noun-verb collocation must be anomalous, etc).

As this suggests, your thinking is likely to become increasingly and differently abstract at each stage. None is simple. Even the first requires you to make a judgement about what counts as familiar, while also relying on your implicit understanding of what counts as a word in the lexicon of English. You then need to draw on a differently abstract set of categories — the parts of speech — and your grasp of what makes a well-formed English sentence (e.g. verb-noun agreement). And, finally, you need to abstract from the logico-semantic specifics of Chomsky’s original to replicate those more subtle relations convincingly. Following this process, you would reject a sentence like ‘Old white men doze regularly’ because it fails at the third stage; whereas you might accept ‘Odourless aromatic principles stagger lucidly’ as a viable addition to the Chomsky canon.

2. Chomsky intended his exemplar to clarify the distinction between syntax and semantics — though nonsensical the sentence is well formed — but it is telling that you need, at the final stage, to consider English word meanings and to draw on some common-sense knowledge of the world. Chomsky also believed the sentence made ‘any statistical model of grammaticalness’ and language learning doubtful (1957, 16), lending further support to his larger claims about a supposedly innate universal grammar. As his response to LLM’s like ChatGPT indicates, this hypothesis continues to guide his thinking. ‘The human mind is not, like ChatGPT and its ilk, a lumbering statistical engine for pattern matching,’ he wrote in an op-ed for the New York Times in March 2023: ‘A young child acquiring a language is developing — unconsciously, automatically and speedily from minuscule data — a grammar, a stupendously sophisticated system of logical principles and parameters. This grammar can be understood as an expression of the innate, genetically installed “operating system” that endows humans with the capacity to generate complex sentences and long trains of thought.’

3. The growing capabilities of these ‘lumbering statistical engines’ make Chomsky’s much-debated hypothesis look increasingly untenable. Without being fed any grammatical rules, they are able not simply to get, say, subject-verb dependency for adjacent words — so ‘men doze’, not ‘men dozes’ — but to simulate ‘applying the rule’ when the subject and verb are separated by some distance — ‘men in the leaky boat owned by Noam Chomsky doze.’ While the first case involves simple next word prediction, a relatively easy bi-gram calculation for a probabilistic system trained on huge linguistic corpora, the second is trickier, given the gap and the complicating introduction of two additional nouns. As Steven T. Piantadosi, one of Chomsky’s latest critics, puts it, these ‘engines’ successfully get ‘the structure of the sentence — the exact thing that statistical models weren’t even supposed to know!’ (2023, 16). Piantadosi’s evidence? He asked ChatGPT to generate other sentences like Chomsky’s exemplar and got results like the following:

Purple fluffy clouds dream wildly.

Green glittery monkeys swing energetically.

These may be lexically and grammatically correct (so successful at stages one and two) but they are otherwise not very convincing, as Piantadosi acknowledges. The bi-grams are ‘not entirely low-frequency’, he notes, and the sentences, while well-formed, are not ‘wholly meaningless’, no doubt ‘because meaningless language is rare in the training data’ (16).

4. Piantadosi is probably right about the training, but ChatGPT’s failure to rise to the challenges of stage three suggest something more about the limits of LLMs in their current form. My own initial prompt using ChatGPT-4 yielded the following:

Silent loud dreams whisper sharply.

Solid liquid thoughts merge tightly.

With the contradictory adjectives and the anomalous noun-verb collocation, these attempts represent a step up — the noun-verb relationship can, of course, always be figural, think ‘green ideas’ since the 1970s. Yet these efforts still fail at stage three because the adverbs are too coherent. When criticized for this, OpenAI’s opaque token calculator lost track of the five-word requirement, proposing ‘Frozen heat shivers coldly’ and ‘Quiet thunder listens silently’ instead, so making a bad situation worse, failing at all three stages. What this suggests is not simply that there is too little nonsense in the training data, but that, as an LLM, ChatGPT can only create sense-making sentences that appear to be ‘thought-through’ and ‘well-informed’. It cannot at the same time do everything required at stage three: analyse sentences logically, check them against an appropriate database of real-world, let alone common-sense, knowledge, keep track of multiple requirements or criteria, etc. Hence the problem of ‘hallucinations‘ (a dubiously humanizing metaphor) and OpenAI’s caveat: ‘ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important info.’ Hence too the growing recognition, based partly on these technological developments, of the distinction between language and thought and of the need for LLMs to link with other modules and plug-ins if they are to become less ‘lumbering’ and more creatively analytical in the best human sense. So, while LLMs tell us more about the statistical processes of early language learning than Chomsky has ever been willing to countenance, they also indicate that as large, exclusively language models, they are still some way from becoming as generative, multi-modal, and interconnected as human minds.