Literary studies in universities must be re-founded as the study of creativity in language because this formulation addresses, in a single conceptual shift, the subject’s historical impasses, its present institutional fragility, and its future intellectual responsibility. It relocates creativity from a reified property of privileged works or subjects to an emergent phenomenon recognised through judgement in linguistic practice.

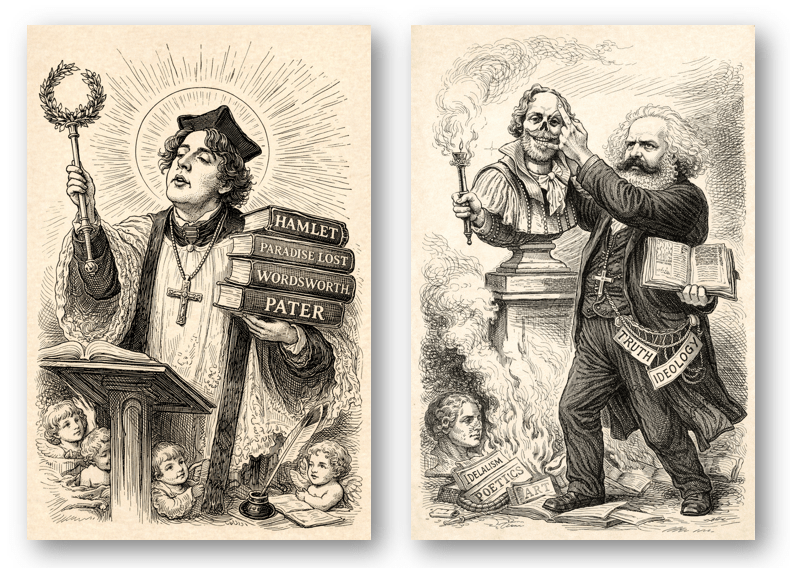

Historically, literary studies secured its authority by appealing to canons, national languages, and ideals of capital-A Aesthetic autonomy. These frameworks presupposed a stable object (‘literature’) and a corresponding figure of authority: the critic as ‘the one who knows,’ whether as guardian of value or as demystifying critiquer. Later theoretical movements productively unsettled these certainties but often at the cost of coherence, dispersing creativity into ideology, discourse, or culture while leaving unresolved the question of what judgement itself consists in.

Re-founding the subject around creativity in language gets beyond this impasse. Conceptually, it avoids treating creativity as a determinate linguistic capacity (‘linguistic creativity’) and instead situates it in the interaction between norms and their transformation. This aligns literary studies with a reclaimed version of Kantian reflective judgement: creativity is not identified by applying rules, concepts, or ready-made ‘approaches’ but discerned where they fail, or need to be re-made. The subject then becomes centrally concerned with how meaning, form, and value emerge without guarantees.

“Creativity as the interaction between norms and their transformation”

This shift is especially necessary today. Digital media, globalised languages (especially English), and AI-generated text have rendered untenable any model that treats creativity as an exclusively human possession or as a stable property. At the same time, algorithmic systems increasingly mimic expertise, threatening to outcompete criticism understood as the delivery of hidden (priestly or heretical) knowledge. In an age of searchable archives and generative machines, literary studies will survive not by knowing more, but by judging more reflexively.

Building this into the subject requires abandoning the legacy of the critic as epistemic authority. In the study of creativity in language, the critic is neither priest nor heretic, neither canonizer nor unmasker. Criticism becomes a public practice of reflective judgement: articulating why something counts as creative, how it works, and what is at stake, without claiming privileged access to truth. Authority shifts from knowledge possessed to reflective judgement exercised and shared.

Re-founded in this way, literary studies regains focus and reach. It dissolves rigid boundaries between literary and non-literary language while preserving its distinctive concern with judgement under uncertainty. Far from weakening the subject, the study of creativity in language makes it newly indispensable in a world where language is everywhere generative, yet meaning and value remain contested.

“Authority shifts from knowledge possessed to reflective judgement exercised and shared”

Whether such a re-foundation is possible within contemporary universities remains an open question. Managerial governance, metric-driven evaluation, and short-term instrumental rationales sit uneasily with a subject centred on reflective judgement, uncertainty, and non-algorithmic forms of evaluation. Universities increasingly reward expertise that can be standardised, audited, and automated, whereas the study of creativity in language resists precisely these forms of capture.

Yet this tension may also be what makes the project viable. As higher education becomes more technocratic, the capacity to sustain practices of judgement that cannot be reduced to metrics becomes institutionally scarce and therefore intellectually distinctive. The possibility of re-founding literary studies now depends less on institutional goodwill than on the subject’s willingness to articulate its value without appealing to outdated forms of authority. If it ditches the heretics along with the priests and presents itself not as a repository of disciplinary skills and knowledge but as a space in which the art of judgement is practised under conditions of uncertainty, it may yet secure a necessary—if fragile—place within the university of the future.